Living Buildings: How Vernacular Architecture Creates Spaces That Breathe with Nature

Modern glass towers and steel frames dominate our cities, but there’s another world of building wisdom that has worked with nature for thousands of years. Vernacular architecture reveals its true value through careful observation of how buildings connect with natural systems. Think about the wind towers in Persian courtyards, found in the magnificent architectural heritage of Iran. These structures create cooling breezes through simple physics – no electricity needed. Or consider the timber-framed buildings of Scandinavian architecture, which capture precious daylight through windows positioned to work with Nordic light patterns.

What Is Vernacular Architecture and Why Does It Matter Today?

Vernacular architecture represents humanity’s smartest response to local environmental challenges. These buildings were created by generations of builders who couldn’t rely on mechanical systems to fight natural conditions. Unlike the globally standardized building styles that came with industrialization, vernacular buildings speak the local language of climate, available materials, and cultural practices.

The Foundation of Climate-Responsive Design

Climate-responsive architecture starts with understanding your environment. Traditional builders knew their local weather patterns better than meteorologists. They built thick adobe walls in hot climates and steep roofs in snowy regions. Every design decision came from centuries of testing what worked and what didn’t. This practical knowledge created buildings that naturally stayed comfortable year-round.

The importance of vernacular architecture isn’t just about pretty buildings – though they certainly are beautiful. It’s about proven ability to create comfortable homes using minimal energy. The thick adobe walls of Southwestern pueblos maintain steady indoor temperatures through thermal mass principles that today’s architects are rediscovering through expensive computer simulations. The raised structures of Southeast Asian stilt houses handle flooding while promoting natural ventilation – strategies that inform today’s coastal development guidelines.

Environmental Intelligence Embedded in Traditional Buildings

What makes vernacular architecture different from old building techniques is its embedded knowledge about local ecosystems. These buildings were designed by people who understood that survival meant working with environmental forces, not against them. A traditional courtyard house in Morocco doesn’t fight desert heat – it choreographs air movement to create cooling zones. A traditional Japanese house doesn’t resist humidity – it breathes and flexes with moisture changes without falling apart.

Contemporary sustainable design standards like LEED and BREEAM now recognize that many vernacular strategies outperform high-tech alternatives. The passive cooling systems of Middle Eastern wind catchers, the thermal regulation of European thatched roofs, and the earthquake resistance of traditional Japanese joinery represent sophisticated engineering that modern practice is still learning to measure and copy.

How Vernacular Architecture Differs From Modern Building Practices

The main difference between vernacular and modern architecture lies in how they handle environmental challenges. Modern architecture, born from the Industrial Revolution’s promise of technological control, tries to create the same indoor conditions regardless of what’s happening outside. Vernacular architecture accepts environmental variables as design drivers, creating buildings that perform differently across seasons – not as a bug, but as a feature.

Energy Use and Environmental Control

Compare a contemporary office tower with a traditional courtyard complex. The tower needs constant mechanical ventilation, artificial lighting during the day, and year-round climate control to maintain consistent conditions in its sealed envelope. The courtyard complex controls indoor conditions through passive strategies: thick walls delay heat transfer, strategically placed openings direct breezes, covered walkways provide shade while allowing air movement, and water features add evaporative cooling where needed.

This difference extends to how materials are used. Modern construction treats materials as abstract components – steel provides structure, glass provides transparency, insulation provides thermal resistance. Vernacular building recognizes that materials behave differently under varying conditions and designs systems that use these behaviors. Timber expands and contracts with humidity changes. Stone absorbs heat during the day and releases it at night. Clay plasters regulate indoor humidity through natural moisture absorption.

Time, Adaptation, and Structural Wisdom

The time factor reveals another major difference. Modern buildings are designed for peak performance on opening day, with maintenance schedules aimed at preserving initial conditions. Vernacular buildings are designed to improve with age – timber structures settle into more stable configurations, adobe walls become denser through weathering cycles, and thatched roofs develop protective layers that improve water resistance.

Most importantly, vernacular architecture embeds regional identity through material choices and construction techniques that reflect local resources and skills. While modern architecture can look virtually identical from Dubai to Detroit, vernacular buildings carry the geological, climatic, and cultural signatures of their specific places, creating architectural diversity that mirrors biological diversity.

Key Characteristics of Vernacular Buildings

Vernacular buildings share certain fundamental characteristics that distinguish them from both historical monuments and contemporary construction. These characteristics represent practical responses to universal human needs – shelter, comfort, durability – achieved through locally specific means.

1. Local Materials and Resource Efficiency

Material responsiveness stands as perhaps the most defining characteristic. Vernacular builders selected materials not just for availability and cost, but for their performance under local conditions. Desert builders chose materials with high thermal mass and low thermal conductivity. Coastal builders selected materials resistant to salt corrosion and wind loading. Mountain builders prioritized materials that could handle freeze-thaw cycles and snow loads. This material intelligence created buildings that literally belonged to their landscapes.

Local materials also meant shorter transportation distances and lower environmental impact. Traditional building techniques used what was available within walking distance. This created buildings that reflected their geological context – limestone houses in limestone regions, timber buildings in forests, adobe structures in clay-rich areas. The building materials told the story of the land.

2. Passive Environmental Control Systems

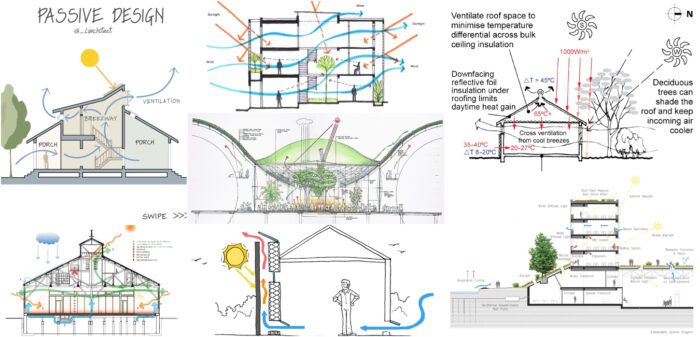

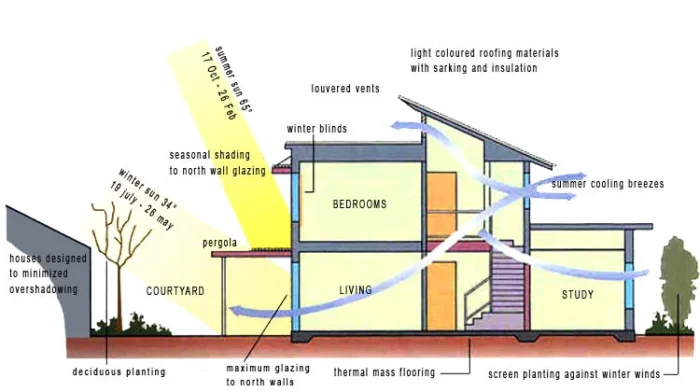

Passive environmental control systems represent another universal characteristic. Before mechanical heating and cooling, comfort depended on understanding how buildings could capture, redirect, and moderate natural energy flows. Traditional buildings demonstrate sophisticated knowledge of solar geometry, prevailing wind patterns, and seasonal climate variations. The orientation of rooms, the sizing of openings, and the massing of structures all contribute to passive thermal regulation that works without external energy inputs.

Natural ventilation systems in vernacular buildings often outperform mechanical alternatives. Cross-ventilation, stack ventilation, and wind-driven ventilation all work together to move air through buildings. These systems respond automatically to changing conditions – stronger winds create more air movement, cooler temperatures reduce the driving forces for ventilation.

3. Incremental Adaptability and Flexibility

Incremental adaptability characterizes how vernacular buildings evolve over time. Unlike modern buildings designed as complete systems, traditional structures were conceived as frameworks that could be modified as needs changed. Rooms could be added, openings could be enlarged or reduced, and internal configurations could be reconfigured without compromising structural integrity. This flexibility allowed buildings to serve multiple generations while adapting to changing family sizes, economic conditions, and functional requirements.

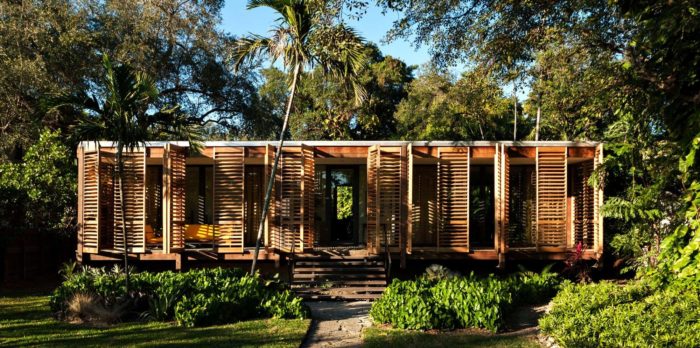

This adaptability also extended to seasonal changes. Many traditional buildings included moveable elements – screens, shutters, panels – that could be reconfigured for different weather conditions. Summer configurations might maximize airflow and shade, while winter arrangements could trap heat and block cold winds.

4. Integrated Water Management

Integrated water management appears consistently across different vernacular traditions. Whether through the sophisticated roof drainage systems of Japanese architecture, the carved channels that direct rainwater in Mediterranean buildings, or the raised foundations that manage flooding in tropical regions, traditional buildings incorporate water as a design element rather than treating it as a problem to be excluded.

Water features in vernacular buildings often serve multiple functions. Courtyards might include fountains or pools that provide evaporative cooling while creating pleasant sounds and visual interest. Roof systems might collect rainwater for household use while protecting the building from weather. These integrated approaches treated water as a resource to be managed, not a threat to be eliminated.

5. Human-Scaled Proportions and Community Safety

Human-scaled proportions reflect the fact that vernacular buildings were constructed by human labor using hand tools. This constraint created architecture with natural proportional relationships that feel comfortable to human occupants. Room dimensions, ceiling heights, and opening sizes reflect the reach of human arms, the height of human bodies, and the scale of human social interactions.

These proportions also reflected the social and cultural needs of their users. Room sizes and arrangements supported extended families, craftwork, and community gathering. The scale of buildings reflected the resources available to their builders and the social structures of their communities. Traditional construction also followed essential construction safety guidelines passed down through generations, ensuring structures could withstand local hazards while protecting the craftspeople who built them.

The Bio-Climatic Intelligence of Living Buildings

Calling vernacular buildings “living” architecture goes beyond metaphor. These structures demonstrate genuine responsiveness to environmental conditions, adjusting their performance characteristics in response to seasonal changes, daily temperature cycles, and varying weather patterns. This bio-climatic intelligence represents perhaps the most sophisticated aspect of traditional building design.

Daily Thermal Cycles and Responsive Performance

Traditional Middle Eastern courtyard houses show this living quality through their thermal performance cycles. During hot days, the thick masonry walls absorb heat slowly, maintaining cool interior conditions while the courtyard creates an updraft that draws air through surrounding rooms. As evening approaches and exterior temperatures drop, the stored thermal mass in the walls begins releasing heat to interior spaces, providing warmth during cool desert nights. This daily breathing cycle requires no mechanical systems, no energy inputs, and no maintenance – yet it provides better comfort than many mechanically conditioned buildings.

The hygroscopic properties of traditional materials contribute another dimension of environmental responsiveness. Clay plasters, lime mortars, and natural fiber insulation all interact with atmospheric moisture, absorbing excess humidity during wet periods and releasing it during dry conditions. This natural humidity regulation prevents the condensation problems that plague many contemporary buildings while maintaining interior comfort levels that mechanical dehumidification systems struggle to achieve.

Seasonal Adaptation and Transformation

Seasonal adaptability represents a more complex aspect of bio-climatic intelligence. Traditional Japanese houses incorporate removable panels and sliding screens that allow radical reconfiguration of interior-exterior relationships. Summer configurations maximize cross-ventilation and shade while winter arrangements optimize solar heat gain and wind protection. The building literally transforms its environmental relationship as conditions change.

This seasonal adaptation extends to the building’s relationship with its site. Deciduous trees planted near buildings provide shade during summer months when leaves are full, then allow solar heat gain during winter when branches are bare. Gardens and courtyards might be configured differently for wet and dry seasons, with water features more prominent during hot months and wind protection more important during cold periods.

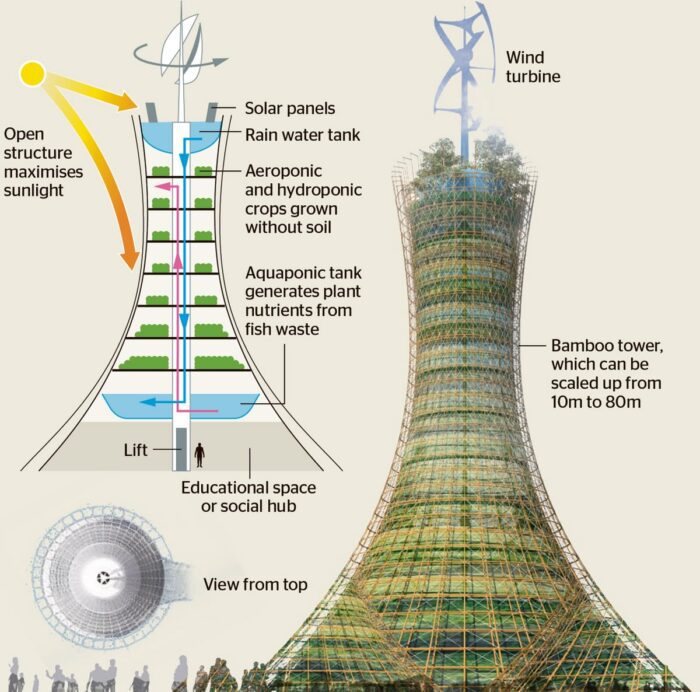

Integrated Vegetation and Natural Systems

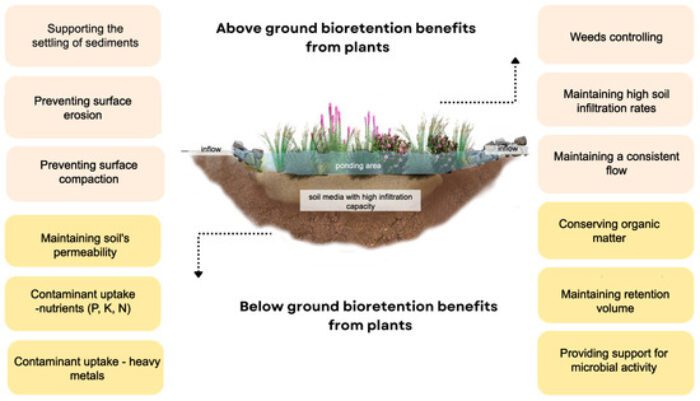

The integration of vegetation into vernacular building systems creates another layer of bio-climatic performance. Climbing plants provide seasonal shading that automatically adjusts to solar angles – dense foliage during summer months when shade is needed, bare branches during winter when solar heat gain is desirable. Roof gardens provide insulation while managing stormwater runoff. Courtyard plantings create evapotranspiration that cools surrounding air naturally.

Cross section of infiltration/recharge BRs type with above-ground and below-ground bioretention benefits of plants

These integrated systems worked because they were designed holistically. The building, its immediate landscape, and its water systems all worked together to create comfortable microclimates. This integration meant that buildings didn’t just sit on their sites – they participated in the local ecosystem.

Advanced Wind Management Strategies

Wind management strategies demonstrate sophisticated understanding of fluid dynamics principles that modern building science has only recently begun to quantify. The wind towers of Persian architecture, the clerestory ventilation systems of tropical buildings, and the strategic placement of openings in Mediterranean houses all demonstrate practical applications of principles that contemporary architects now model using computational fluid dynamics software.

These wind management systems often created multiple zones within buildings with different airflow characteristics. Public spaces might have strong airflow for cooling, while private spaces might have gentler air movement for comfort. The systems automatically adjusted to changing wind conditions, providing more ventilation when needed and less when calm conditions prevailed.

Contemporary Relevance and Future Applications

The relevance of vernacular bio-climatic strategies has grown as contemporary architecture grapples with climate change, resource scarcity, and the environmental costs of mechanical building systems. What were once dismissed as primitive techniques are being recognized as sophisticated solutions that contemporary practice needs to understand and adapt.

Modern Standards and Traditional Wisdom

Passive House standards, now considered advanced in sustainable design, essentially codify principles that vernacular builders understood intuitively. The focus on thermal bridging, air tightness, and thermal mass optimization directly parallels strategies found in traditional construction. The difference lies in the precision of contemporary measurement and the ability to optimize performance through computer modeling – but the basic principles remain unchanged.

Green building certification systems increasingly recognize vernacular strategies. Points are awarded for daylighting strategies that traditional builders used automatically. Natural ventilation systems that were standard practice in vernacular buildings are now innovative features in contemporary construction. The integration of natural systems that defined traditional architecture is now called biophilic design.

Resilience and Climate Adaptation

Biophilic design, currently gaining recognition as essential for human health and productivity, finds its fullest expression in vernacular architecture that never separated interior and exterior environments. The visual connections to nature, the use of natural materials, and the integration of natural light and ventilation patterns that biophilic design promotes were simply standard practice in traditional building.

Contemporary architects are developing hybrid approaches that combine vernacular principles with modern capabilities. Thermal mass strategies informed by traditional desert architecture are being optimized through phase-change materials. Natural ventilation systems based on traditional models are being enhanced with smart controls that respond to real-time environmental conditions. Building-integrated photovoltaics are being designed to function like traditional roof overhangs, providing weather protection while generating renewable energy.

Material Innovation and Environmental Impact

The challenge for contemporary practice lies not in wholesale adoption of historical techniques, but in understanding the environmental intelligence embedded in vernacular solutions and translating it into approaches suitable for current conditions. This requires moving beyond surface aesthetics to engage with the fundamental logic of bio-climatic design.

The growing recognition of embodied carbon in building materials makes vernacular approaches increasingly relevant. Traditional buildings typically used locally sourced materials with minimal processing, resulting in extremely low embodied energy compared to contemporary alternatives. As lifecycle carbon assessments become standard practice, the environmental advantages of vernacular material strategies become undeniable.

Resilience and Climate Adaptation

Resilience planning for climate change adaptation also highlights vernacular wisdom. Traditional buildings in hurricane-prone regions, flood-prone areas, and seismically active zones demonstrate time-tested strategies for surviving extreme events. Contemporary resilient design guidelines increasingly reference vernacular precedents that have weathered decades or centuries of environmental challenges.

The integration of vernacular principles into contemporary practice requires sophisticated understanding of both traditional techniques and modern performance requirements. This hybrid approach promises architecture that combines the environmental intelligence of vernacular design with the precision and capabilities of contemporary building science – creating truly living buildings that breathe with nature while meeting 21st-century performance standards.

Vernacular architecture offers more than historical curiosity or aesthetic inspiration. It provides a practical framework for creating buildings that work with natural systems rather than against them, achieving human comfort through environmental collaboration rather than mechanical domination. As contemporary practice seeks sustainable alternatives to energy-intensive building systems, the bio-climatic intelligence of vernacular design emerges not as a relic of the past, but as a blueprint for the future of environmentally responsive architecture.

What makes vernacular architecture sustainable?

Vernacular architecture achieves sustainability through local material use, passive climate control, and designs that work with natural systems rather than against them. These buildings typically have extremely low embodied carbon because they use minimally processed materials sourced within walking distance. The passive heating and cooling strategies require no external energy inputs, while the bio-climatic design responds automatically to seasonal changes.

Can vernacular architecture work in modern cities?

Absolutely. Contemporary architects are successfully adapting vernacular principles for urban contexts through hybrid approaches. Examples include modern courtyard houses that use traditional ventilation strategies, office buildings with wind towers for natural cooling, and residential towers with integrated vegetation for seasonal shading. The key is translating traditional wisdom into solutions that meet current building codes and performance standards.

What are the most important lessons from vernacular architecture?

The primary lessons include: working with climate rather than fighting it, using local materials to reduce environmental impact, designing for passive comfort before active systems, creating buildings that improve with age, and integrating structures with their immediate ecosystem. Perhaps most importantly, vernacular architecture teaches us that buildings should be context-specific rather than globally standardized.

How do vernacular buildings handle extreme weather?

Traditional buildings demonstrate remarkable resilience through time-tested strategies. In hurricane regions, steep roofs and reinforced connections prevent wind damage. Flood-prone areas use raised foundations and water-resistant materials. Earthquake zones employ flexible joinery and lightweight construction. These strategies have evolved through centuries of trial and error, creating buildings that survive conditions that damage modern structures.

Vernacular architecture offers more than historical curiosity or aesthetic inspiration. It provides a practical framework for creating buildings that work with natural systems rather than against them, achieving human comfort through environmental collaboration rather than mechanical domination. As contemporary practice seeks sustainable alternatives to energy-intensive building systems, the bio-climatic intelligence of vernacular design emerges not as a relic of the past, but as a blueprint for the future of environmentally responsive architecture.

Tags: bio-climatic designbio-climatic-architectureclimate-responsive architectureclimate-responsive designEnvironmental Designenvironmental-architectureGreen Buildingindigenous-architectureliving buildingslocal materialsnatural ventilationpassive designpassive environmental controlSustainable ArchitectureSustainable DesignThermal Masstraditional architecture vs modernTraditional building techniquestraditional-buildingsVernacular Architecture

Ruba Ahmed, a senior project editor at Arch2O and an Alexandria University graduate, has reviewed hundreds of architectural projects with precision and insight. Specializing in architecture and urban design, she excels in project curation, topic selection, and interdepartmental collaboration. Her dedication and expertise make her a pivotal asset to Arch2O.