The Science Behind Floating Buildings: How Tensegrity Structures Defy Gravity

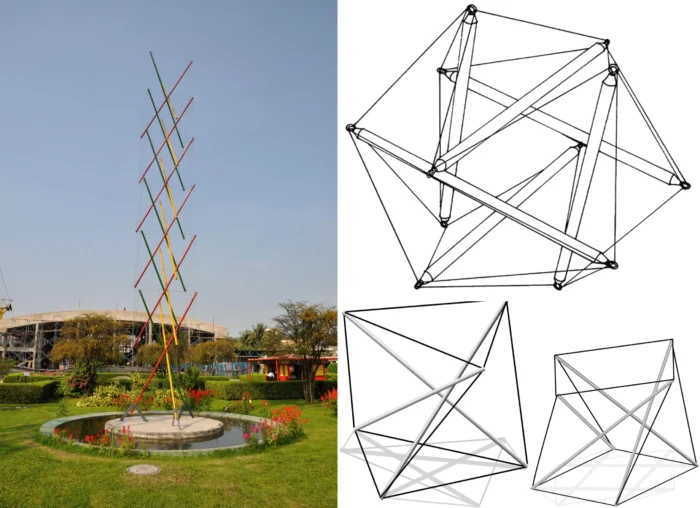

Walk up to Kenneth Snelson’s Needle Tower and you’ll see something that breaks every rule about buildings. Thirty feet of aluminum tubing hangs in mid-air, somehow staying put through a careful balance of push and pull forces that would have baffled ancient builders. This is tensegrity at work—a building method so strange that it took architects and engineers decades to figure out how it actually works.

I’ve spent years watching how building systems change over time, and tensegrity ranks among the biggest shifts since steel frames appeared. You won’t find the heavy stone blocks of Gothic churches here, or even the new materials we’re experimenting with today. Instead, tensegrity buildings stay strong through what looks impossible—rigid pieces that never touch each other, held up by a web of cables that spread weight across the whole structure.

Buckminster Fuller called this “tensional integrity,” and he was right to give it a special name. While normal buildings pile up mass and squeeze materials together, tensegrity systems get their strength from opposing forces working against each other. It’s like biology meets engineering, with connections to today’s computer-designed buildings that most people miss.

What Is a Tensegrity Structure in Architecture?

Tensegrity structures deserve a spot next to the greatest building innovations in history. These systems put separate pieces under compression inside a continuous network of tension cables. The result? Buildings that seem to float while staying rock-solid.

The Historical Break from Traditional Building

Think about how we’ve always built things. Ancient Greeks stacked stone blocks. Medieval builders added flying buttresses to push harder against their walls. Even steel construction still depends on columns and beams touching each other in predictable ways. Tensegrity throws all that out the window.

Fuller combined “tension” and “integrity” back in the 1960s to describe buildings that get their strength from stretched cables instead of compressed stone or steel. This goes against thousands of years of building tradition. From Egyptian pyramids to modern skyscrapers, architecture has always meant piling up heavy materials and managing compression. Tensegrity makes the cables do the heavy lifting while the rigid pieces just float in space.

Why This Matters for Modern Architecture

When structural engineer David Geiger described tensegrity as “discontinuous compression and continuous tension,” he was pointing to something revolutionary. Your typical building depends on solid connections between parts. Break one connection, and you might bring down the whole thing. Tensegrity systems spread the load so evenly that losing one piece just makes the rest adjust without failing.

This isn’t just engineering theory. The real-world examples show buildings that use less material, weigh less, and can handle forces that would damage conventional structures.

How Do Tensegrity Structures Work?

The mechanics behind tensegrity reveal why these buildings represent some of the smartest engineering ever developed. Regular buildings send loads through predictable paths—down the columns, across the beams, into the foundation. Tensegrity structures scatter forces throughout their entire network, creating what engineers call “global stiffness” through parts that can move and flex.

The Role of Prestress in Structural Stability

The secret lies in prestress—putting tension in the cables before the building even carries any weight. This creates a balanced system where compression elements push outward against the cable network while the cables pull inward. The structure holds its shape through this constant tug-of-war, staying stable even when outside forces try to disturb it.

This works completely differently from normal construction. Take out a column in a steel building and you’re asking for trouble as the remaining parts try to carry extra weight. Remove a piece from a well-designed tensegrity structure and the whole network adjusts, redistributing forces while keeping the building stable.

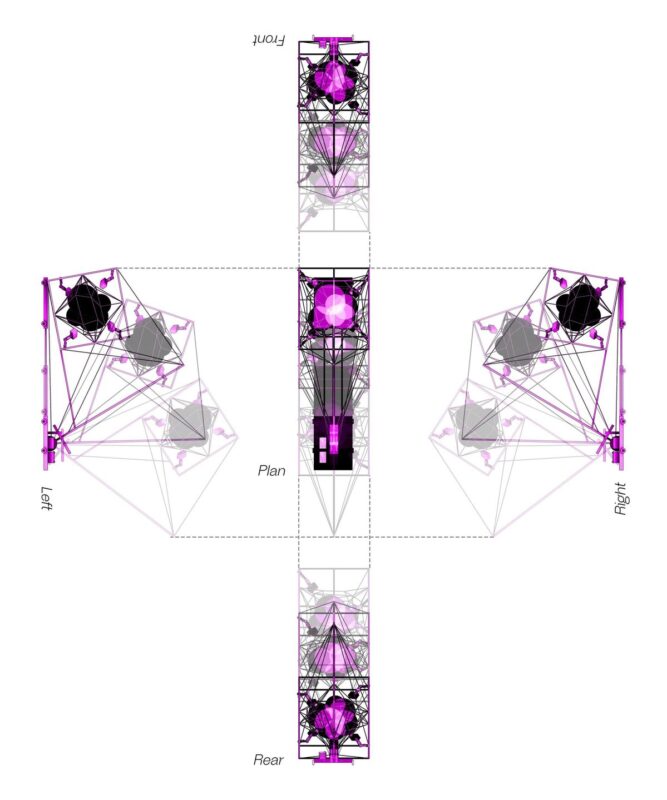

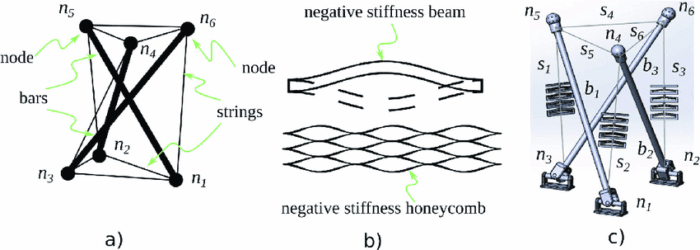

a) Simple three-bar tensegrity structure with six nodes and nine strings, b) negative stiffness beam (top) and an array of these beams forming a NSH (bottom), c) 3D model of the three-bar tensegrity integrated with three NSHs.

Mathematical Elegance Meets Practical Efficiency

The math behind tensegrity systems is beautiful in its efficiency. Regular buildings need safety factors of 2.5 or higher because stress concentrates at weak points. Tensegrity structures can work with lower safety factors because they spread stress more evenly. Less safety margin means less material, which means less environmental impact.

You can see this efficiency in action. The forces don’t pile up at single points like they do in beam-and-column construction. Instead, they flow through the entire network, making every piece contribute to the building’s strength.

What Are the Advantages of Tensegrity Structures?

After watching different building systems develop over decades, I can say tensegrity offers solutions to some of architecture’s biggest challenges. The benefits go beyond just structural performance—they touch on sustainability, flexibility, and how buildings can express new ideas about design.

Exceptional Strength-to-Weight Performance

Regular buildings spend most of their strength just holding themselves up. That’s dead weight—material you need but that doesn’t help the building do its job. Tensegrity structures flip this around, achieving huge spans with minimal material. Take Brisbane’s Kurilpa Bridge: it stretches 470 meters but uses way less steel than a conventional bridge of the same size.

This material efficiency directly cuts environmental impact. When you need less steel, concrete, and other materials, you reduce the carbon footprint of construction. The potential for factory prefabrication and modular assembly makes this even better for sustainable building.

Adaptability and Responsive Design

Rigid buildings resist change. Tensegrity networks embrace it. The same structure can handle different shapes and loads while keeping its integrity. This opens doors for buildings that respond to weather, occupancy, or changing needs over time.

The adaptive building skin projects we’re seeing today hint at this potential. Buildings that can adjust their form based on environmental conditions or user requirements aren’t science fiction—they’re the logical next step for tensegrity systems.

Who Invented Tensegrity Structures?

The story of tensegrity’s invention shows how the best innovations often come from unexpected places. While Buckminster Fuller gets most of the credit, the real story involves artists, scientists, and engineers working together in ways that none of them initially planned.

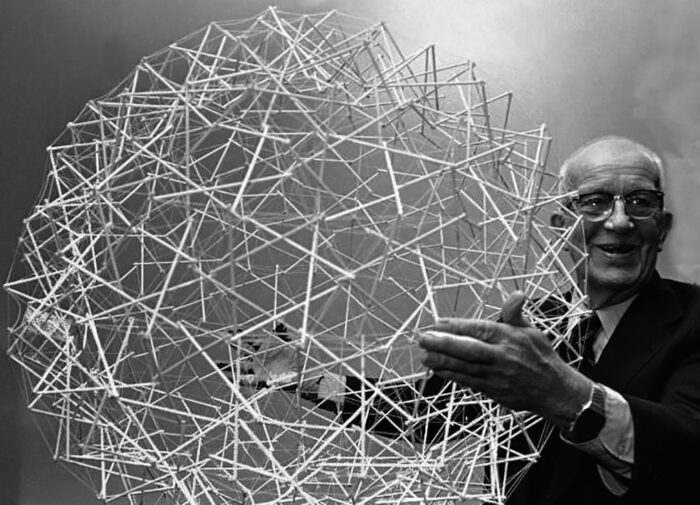

Kenneth Snelson’s Artistic Discovery

The first tensegrity structure wasn’t designed by an engineer. Kenneth Snelson created his “X-Piece” in 1948 while studying art at Black Mountain College. He was exploring sculpture, not trying to revolutionize architecture. But his piece demonstrated something nobody had seen before: rigid elements floating in space, held stable by cables that never let the solid parts touch.

Snelson saw this as art. He probably didn’t realize he’d just discovered a new way to build things that would influence architecture for decades to come.

Fuller’s Theoretical Framework

Fuller recognized what Snelson had stumbled onto. He developed the math and theory that turned an art project into a building system. His 1962 patent for “Tensile-Integrity Structures” gave engineers the tools they needed to scale tensegrity from sculptures to real buildings.

The collaboration between Fuller and Snelson wasn’t always smooth—they later disagreed about who deserved credit for what. But their partnership shows something important about innovation: the best ideas often emerge when different disciplines cross paths. Gothic cathedrals came from combining spiritual goals with engineering necessity. Tensegrity emerged from mixing artistic experimentation with scientific analysis.

What Are Examples of Tensegrity Buildings?

Tensegrity principles have been applied to everything from small pavilions to major infrastructure projects. Each application teaches us something different about how these systems can work in the real world.

The Kurilpa Bridge: Infrastructure Scale Tensegrity

Brisbane’s Kurilpa Bridge remains the most ambitious tensegrity project ever built. This 470-meter pedestrian bridge, completed in 2009, proves that tensegrity can handle serious infrastructure requirements. The mast-and-cable system creates a profile that changes throughout the day as light conditions shift. More importantly, the structure responds to wind and pedestrian loads through controlled movement rather than rigid resistance.

The bridge cost more than conventional alternatives, but it demonstrated possibilities that engineers are still exploring. The lessons learned from Kurilpa continue to influence cable-stayed bridge design worldwide.

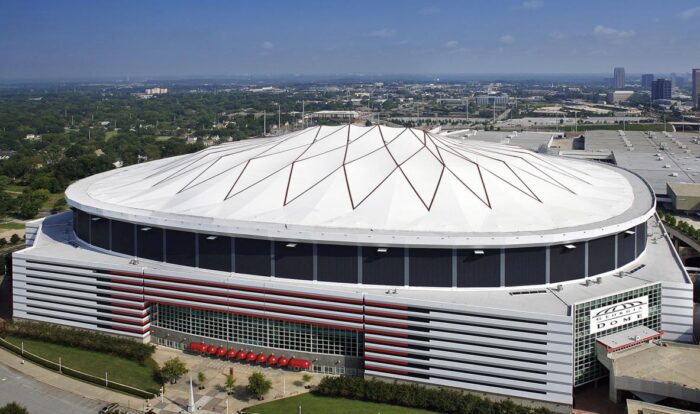

David Geiger’s Tensegrity Domes

The Georgia Dome, completed in 1992, showed how tensegrity principles could create massive enclosed spaces. Geiger’s cable-stayed system achieved a 240-meter clear span using far less material than conventional dome construction. Though the dome was demolished in 2017, its influence on large-span structures continues.

The dome’s success proved that tensegrity could work for major public buildings, not just experimental structures. It paved the way for sports facilities, exhibition halls, and other large spaces that need to cover huge areas without internal supports.

Contemporary Applications and Hybrid Systems

Today’s architects are finding new ways to apply tensegrity principles. Renzo Piano’s Centre Pompidou-Metz uses tensegrity-like concepts in its timber gridshell roof, achieving remarkable spans with minimal material. While not a pure tensegrity structure, it shows how these principles can inform hybrid approaches that combine different structural systems.

The diversity of contemporary architectural approaches demonstrates how tensegrity concepts can adapt to different cultural contexts and climate conditions while maintaining their structural advantages.

How Strong Are Tensegrity Structures?

The strength of tensegrity structures challenges conventional thinking about structural performance. Traditional analysis looks at maximum stress points—where a beam bends most or where columns carry the heaviest loads. Tensegrity systems require completely different approaches that account for their unique load distribution characteristics.

Global Load Distribution vs. Local Stress Concentrations

Regular structures develop stress concentrations at predictable locations. A beam stressed to its limit will fail at mid-span or at support points. Tensegrity structures spread loads throughout their network, creating more even stress distribution that can handle higher overall loads despite using less material.

This distribution effect becomes crucial under dynamic loading. Earthquakes and wind loads that would damage conventional buildings get absorbed by the entire tensegrity network. The structure can deform in controlled ways without losing stability, potentially offering better performance than rigid buildings under extreme conditions.

The Critical Role of Connections and Pretension

The strength of any tensegrity structure depends on two critical factors: connection quality and maintained pretension. Unlike conventional buildings where connection failure usually causes local damage, connection problems in tensegrity systems can affect the entire structure.

This demands exceptional attention to detail during construction. Every connection must be precisely manufactured and carefully installed. The pretension must be maintained throughout the building’s life, requiring monitoring and adjustment systems that conventional buildings don’t need.

What Materials Are Used in Tensegrity Structures?

Material selection for tensegrity structures reflects their dual nature—compression elements that must resist buckling and tension elements that must maintain consistent force under changing conditions. Getting these materials right represents one of the most critical aspects of tensegrity design.

Compression Elements: Steel, Aluminum, and Beyond

Steel tubing remains the most common choice for compression elements, offering excellent strength-to-weight ratios and well-understood connection details. The material resists buckling effectively and can be fabricated into complex connection geometries that tensegrity systems require.

Aluminum offers weight savings for applications where dead load matters more than cost. Some projects have experimented with timber compression elements, though these require careful attention to moisture and durability concerns. Composite materials promise even better performance, but they’re still expensive for most applications.

Tension Elements: From Steel Cables to Synthetic Materials

The tension elements present more complex challenges. Steel cables work well for static loads, but architectural applications often involve dynamic conditions that require materials able to maintain consistent tension under varying loads. Modern tensegrity buildings increasingly use synthetic cables or tensioned membranes to achieve the necessary performance.

High-strength synthetic materials continue expanding the possibilities. These materials can maintain tension more consistently than steel under temperature changes, and they don’t corrode. Some can even be made translucent, opening new possibilities for tensegrity structures that play with light and transparency.

Connection Hardware: The Make-or-Break Component

Connection details often determine whether a tensegrity structure succeeds or fails. Traditional structural connections transfer loads through bearing and shear between solid elements. Tensegrity connections must handle complex force directions while accommodating the movement that these systems require.

This has driven development of specialized hardware designed specifically for tensegrity applications. These connections must be precisely manufactured and carefully installed, but they enable the complex geometries that make tensegrity structures possible.

The elegance of tensegrity buildings lies in their fundamental challenge to how we think about construction. These structures force us to reconsider basic assumptions about stability, strength, and even what buildings should look like. They achieve stability through dynamic balance rather than static mass, offering a glimpse of architecture that works with forces rather than simply resisting them.

As environmental concerns push us toward using less material and creating less waste, tensegrity principles point toward buildings that accomplish more with less. They don’t just carry loads—they negotiate with them, creating structures that can adapt and respond while maintaining the safety and durability that good architecture requires.

This represents the next step in structural evolution. From stone compression to steel frames to tensegrity networks, each advance has enabled new possibilities for what buildings can do and how they can serve human needs. Tensegrity structures don’t defy gravity—they dance with it, creating architecture that feels both impossible and inevitable.

Tags: buckminster fullerBuilding Materialscompression tension systemsinnovative architectureKenneth Snelsonstructural designStructural Engineeringsustainable constructiontensegrity architecturetensegrity structureTensegrity Structures

Emily Reyes is a Brooklyn-based architecture writer and Article Curator at Arch2O, known for her sharp eye for experimental design and critical theory. A graduate of the Southern California Institute of Architecture (SCI-Arc), Emily’s early work explored speculative urbanism and the boundaries between digital form and physical space. After a few years in Los Angeles working with boutique studios on concept-driven installations, she pivoted toward editorial work, drawn by the need to contextualize and critique the fast-evolving architectural discourse. At Arch2O, she curates articles that dissect emerging technologies, post-anthropocentric design, and contemporary spatial politics. Emily also lectures occasionally and contributes essays to independent design journals across North America.