Few architects live long enough to see a building, they designed, make it to the list of protected pieces of heritage. An even fewer number are able to brand their names on that list only two years completing the building.

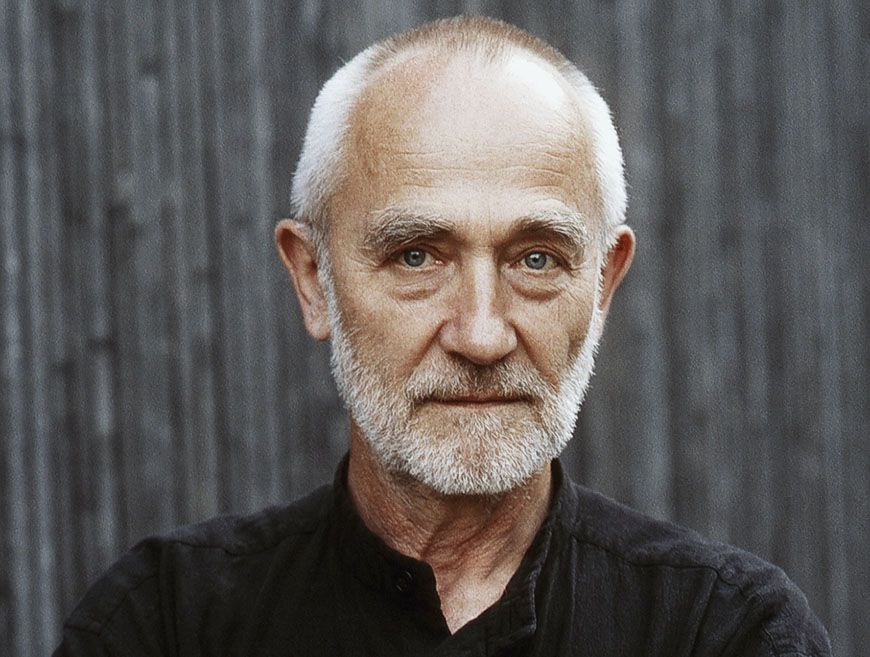

Peter Zumthor is just one of those! Many consider him the most important architect in Switzerland. Others go beyond that and regard him as the most brilliant architect alive at present. The beauty of Zumthor’s work comes from his perfect choice of materials, which are often native. His reluctance to publish his buildings internationally as well as his temper contributed to his fame. Although in the past, he concentrated most of his projects within the Alpine domain, lately they have extended to other countries.

Courtesy of Peter Zumthor

How did Peter Zumthor become an architect?

-

Early Beginnings

The Swiss-born Peter Zumthor spent some of his teenage year’s training to become a carpenter (1958 – 1962). In 1967, he started college where he joined the Kunstgewerbeschule, Vorkurs, Fachklasse, and, later on, Pratt Institute in New York.

In 1967, the government of Switzerland employed him in the department of Monuments Preservation. He worked there as a planning and building consultant and, also, as an architectural expert for historic villages.

-

Career

His career as an architect started after establishing his own practice in 1979. He accepted several teaching positions at colleges like the Academy of Architecture in Universitá Della Svizzera Italiana, Mendrisio. Additionally, he was a visiting professor at the University of Southern California Institute of Architecture and SCI-ARC in Los Angeles. He, also, worked at Harvard Graduate School of Design and the Technische Universität in Munich.

-

Prizes and Awards

Two of his most famous works, which won him many prizes, are Therme Vals in Switzerland as well as Bruder Klaus Kapelle in Germany. Some of the awards he received were:

-

- Carlsberg Architecture Prize, Denmark (1998)

- Mies Van der Rohe Award for European Architecture (1999)

- Thomas Jefferson Foundation Medal in Architecture, University of Virginia, USA (2006)

- Arnold W. Brunner Memorial Prize in Architecture (2008)

- Premium Imperiale, Japan Art Association (2008)

- Pritzker Prize (2009)

- RIBA Royal Gold Medal (2013)

-

Projects

1) Shelters for the Roman archaeological site, Chur, Graubünden, Switzerland (1986)

© AUGUST FISCHER

The excavations in Chur revealed a Roman quarter that comprised three adjacent buildings of different sizes. Zumthor designed wooden structures to envelop these buildings and protect them.

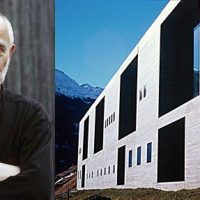

2) Atelier Zumthor, Haldenstein, Graubünden, Switzerland (1986)

Courtesy of Peter Zumthor

Zumthor wished to relocate his practice to what was once a farmhouse and later a former family home. However, the building was fairly dim. The firm tried to come up with a solution to bring more daylight into the building but to no avail. They took a decision to tear it down and construct new premises.

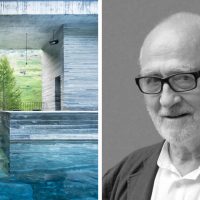

3) Therme Vals, Vals, Graubünden, Switzerland (1996)

Courtesy of Peter Zumthor

The thermal baths became a protected piece of heritage after less than two years of their construction. This is why Therme Vals is Peter Zumthor’s most celebrated work. He transformed a bankrupt hotel into a tourist destination just by including thermal baths in it. Ever since they opened, the baths have been receiving about 40,000 guests a year, and the hotel income has increased by 45%. The baths include concrete walls and cut-to-size Valser Granit. Their 30°C-hot water originates from the mountain behind.

4) Bruder Klaus Kapelle, Mechernich-Wachendorf, Germany (2007)

© Samuel Ludwig

The chapel was constructed in the form of a tent, using 112 big tree logs. The whole building process took 24 days and was done by pouring consecutive layers of concrete around the wooden structure. A fire was intentionally lit inside the building for three weeks to dry out the tree trunks. The drying out process facilitated the stripping of the logs away from the concrete envelope. The design included covering the floor of the church with lead. The builders melted the lead on-site in a crucible and covered the whole floor with it in a manual manner.

- Courtesy of Peter Zumthor

- Courtesy of Peter Zumthor

- Courtesy of Peter Zumthor

- Courtesy of Peter Zumthor

- Courtesy of Peter Zumthor

- Courtesy of Peter Zumthor

- Courtesy of Peter Zumthor

- Courtesy of Peter Zumthor

- Courtesy of Peter Zumthor

- Courtesy of Peter Zumthor

- Courtesy of Peter Zumthor

- Courtesy of Peter Zumthor