Matias del Campo is a registered architect, designer, educator, and director of the AR2IL Laboratory – the Laboratory for Architecture and Artificial Intelligence at the University of Michigan. Founded together with Sandra Manninger in Vienna in 2003, SPAN is a globally acting practice best known for their application of contemporary technologies in architectural production. Their award-winning architectural designs are informed by advanced geometry, computational methodologies, and philosophical inquiry. This frame of considerations is described by SPAN as a design ecology. Most recently Matias del Campo was awarded the Accelerate@CERN fellowship, the AIA Studio Prize, and was elected to the boards of directors of ACADIA. SPAN’s work is in the permanent collection of the FRAC, the MAK in Vienna, the Benetton Collection, and the Albertina. He is an Associate Professor at Taubman College for Architecture and Urban Planning, University of Michigan. Publications include Neural Architecture: Design and Artificial Intelligence (ORO Editions, 2022); Diffusions in Architecture: Artificial Intelligence and Image Generators (Wiley, 2024); and three editions of Architectural Design including Machine Hallucinations: Architecture and Artificial Intelligence (Wiley, 2022) and the forthcoming Artificial Intelligence in Architecture (Wiley, 2024).

With the recent explosion of Artificial Intelligence and the arrival of image, video and music generators onto the art, design and architecture scenes, we sit down with Matias del Campo, a champion of the use of AI to augment traditional design ecologies, to go in-depth about the theoretical implications of such an arrival and how AI will effect architecture in particular. We speak about authorship, tame and wicked problems, aspects of architecture that are difficult to capture in images, and whether AI can (or already has) develop its own sensibilities.

LEFT TO RIGHT: Matias del Campo. Machine Hallucinations: Architecture and Artificial Intelligence (AD). Wiley, 2022; Neural Architecture: Design and Artificial Intelligence. Applied Research & Design ORO Editions, 2022; Diffusions in Architecture: Artificial Intelligence and Image Generators. Wiley, 2024; Artificial Intelligence in Architecture (AD). Wiley, 2024.

One of the questions you pose in your recent publication Neural Architecture is: “can AI create a novel sensibility?” and “if so, can we, as humans, perceive and understand it?”1 How do you define sensibility?

Sensibility can be defined as a collection of different aspects that shape you as a designer throughout your lifetime. The influences, the ideas, the concepts, the aesthetics, the art, the buildings you have seen. The poetry you have read. Memories from your childhood – the colors, the smells, the tastes – all the things somehow shape you as a designer, and form something that is uniquely yours in some way, shape or form. Your individual convictions about ethics and aesthetics. I would argue that this is what constitutes a sensibility. The question of course is, if we, as humans, are shaped by all these epistemological experiences, by all these visuals, by all the smells, the colors, the memories by all the music we have heard in our lifetime, can a machine run a process that basically also devours enormous amounts of data in the form of images, texts, etc., to create something that can be compared to a human sensibility? To that extent it would be interesting to know whether these synthetic sensibilities are unique, or whether they already live within the vast treasure trove of data – within the latent space, in the shadows of existing data points.

To your question whether humans can perceive this novel sensibility or not. This was a thought that emerged very early in the research I was conducting on architecture and AI. What if AI can generate artistic artifacts that are outside the human perception? Ultrasound music, poetry recited in the speed of light, infrared visuals that are outside our range of vision, perfumes that are outside our range of smell. Not perceivable to us, as machines can operate within a range of sensibilities that are not accessible to humans – but machines can perceive them. Their own unique form of culture.

Intertwined with questions as to whether AI can develop its own sensibility, and its potential as a planner and designer, is the story of the 18th century automaton known as the Turk – a supposedly intelligent, chess- playing agent that was later exposed as a scam, housing a human operator within. Is this a metaphor for the current state of AI?

There are several different layers of why the Turk has such a prominent role in the book Neural Architecture. One being that it is a ruse that happened in Vienna, and I had to chuckle at the thought that a fake built in Vienna in the eighteenth century might have inspired a variety of different people around the world to think for the first time about automation and to a larger extent, about artificial intelligence. From Edgar Ellen Poe to Walter Benjamin, the Turk inspired contemplations about the nature of the machine. More importantly, and essential for the debate on AI, was the Turk’s influence on people such as Charles Babbage who constructed the analytical engine (which can be considered the first general purpose computer), Edmund Cartwright who went on to make the first steps towards automation with his power loom and Joseph Marie Jaquard, whose introduction of punch cards as programming device in 1801 is a major milestone. More recently, the name “Turk” was adopted by Amazon for their MTurk service which is designed to provide labeling services necessary to build datasets for supervised machine learning. It is somewhat cynical to name a service that relies on human labour, and human feature recognition capabilities, to provide the building stones of automation. As you can see “The Turk” was the “Ghost in the Machine” all along – albeit a human one. At its very core Artificial intelligence (AI) is an attempt to replicate certain aspects of human cognition, drawing parallels to human creativity and perception. This endeavor is rooted in our understanding of neuroscience, aiming to mimic processes such as dreaming, hallucination, and patterns of neural firing that define human traits. Using mathematical algorithms, AI can simulate human abilities like perception, taste and even smell, essentially employing these capabilities in machine learning systems. However, our comprehension of the human mind is continuously evolving, and historical comparisons likening it to mechanical or computational systems have often been proven inaccurate. Just remember the historical comparison of the mind to mechanical clockwork.

Nevertheless, AI technologies such as machine learning and deep learning provide valuable tools for enhancing human cognition. As noted by Mingyan Liu, the chair of the computer science at the University of Michigan, there’s merit in rebranding AI as “Assisted Intelligence” to underscore its role in amplifying human capabilities rather than merely imitating them.

I would argue that AI serves as a means to expand human understanding and tackle the challenges of tomorrow. It facilitates learning and problem-solving, serving as a partner to human intellect rather than a substitute.

Early methods utilizing AI for image output, such as Google’s Deep Dream and neural network experiments you showcased in Neural Architecture and Machine Hallucinations, often resulted in surreal, blurry, dream- like images. With my own explorations, primarily in Midjourney, I find that each new version brings higher resolution output, but the content itself is more predictable and less … weird. Is there still a chance for “moments of estrangement, and aspects of defamiliarization” in these new tools? Is there still a way to capture “wild features?”

It is clear that those tools are becoming better because the big players in this business providing the models are trying to comply with the requirements of an enormous user base – and most of them want realistic outputs. I call these newer models vanilla models because they’re just profoundly boring. I know a series of artists and architects who are intentionally using older versions of these diffusion AI-models in order to achieve forms of estrangement – these moments, where things are familiar enough to capture our attention, but strange enough to provoke us to think differently about the results. Exploring the dark corners of the latent space, where we can find things, design solutions, ideas, artistic possibilities that are striving away from robust curve fitting, striving away from something that is completely realistic and probable. I like the improbability of things. Sometimes I think that if things have become improbable, or different, or strange or weird they have a higher capacity to provoke you as a viewer, to evoke an emotional response in you. Every good work of art, in my opinion at least, should be capable of evoking a response in the human observer – in the best case an emotional response. Great architecture does exactly that.

Great architecture evokes emotional responses in the user. Imagine yourself entering an evocative space – experience the light, the color, the materiality, the expanse of that space, the way it is constructed, the depth, the height, in combination with strange, unexpected features – a pinch of Surrealism if you like. The newer those diffusion models get, the more boring those results turn out. It is still possible to push those newer diffusion models to do things that are estranged. It has become just more difficult to get there. You have to pu

sh it further. You have to be more aggressive. You have to really combine a variety of different techniques, be very deliberate in finding ways to throw the machine of balance. I would rather prefer instead of me forcing the machine to do something strange, that the machine does this on its own, unsolicited. It is in this unsolicited response, the strange response where artists and architects can find innovations that are different, that are novel to us. They were there all along in the latent space. We just needed to find them.

SPAN’s competition entry for the 24 Highschool competition in Shenzhen, China. This project employed an Attentional Convolutional Neural Network (AttnGAN) as the primary design method. Language prompts such as “This building is pleated and broken into colorful chunks” were used to train the NN to provide images as a starting point for the design. 2020.

We cannot talk about AI today without talking about authorship. You have written on the subject, citing Roland Barthes who stated that meaning resides with language itself and not the author of a text. With AI, in particular prompt-driven image generators, there are other actors involved such as the AI itself, including the authors of the images it was trained on, and the actual output. The notion of authorship here becomes a bit confused …

Well, I don’t think that it is confusing. I think it’s really straightforward. It is probably time that we abandon the term entirely. It is, after all, a rather new term. Authorship emerged after the invention of the printing press in order to be able to differentiate between copies and authored pieces. Before that we had a far more communal idea of creating art. Gothic cathedrals for example. In the vast majority of cases we don’t know the architects of these masterpieces – it was probably many, not just one. The craftsmen who created the jewelry for Tutankhamun, the artists who created the paintings on the walls of Etruscan tombs, Roman artifacts – they are all anonymous. We know a couple of Greek artists, Praxiteles and Zeuxis for example, but the vast majority we don’t know. Is it really important whether we know the name of the person who made the piece of art? Does it reduce the artistic quality of the work if we don’t know the author? If you think about it, the term authorship itself has gone through different iterations and critical watershed moments. For instance the invention of photography in the nineteenth century, which created a moment very similar to what you’re seeing today with AI. During the emergence of photography in the 19th century artists were afraid that they will be pushed out of business, that photography is going to replace them because photography can do portraits much better, faster and cheaper than any human can. We are in a similar moment right now. You know what is interesting? What the arts did when confronted with photography: it adapted. Artistic ideas such as impressionism, expressionism, abstraction, Dada, surrealism – all these ideas would most likely not exist without the invention of photography, because art had to respond with something that photography was not able to do. We had a similar moment when computers were introduced in the artistic process in the 1980ies and 1990ies. I still can hear in my ear people telling me (I was doing electronic music back then) “Well, you just have to press one button, and then the computer does the music for you.” I always answered, “Please show me that button.” The vast majority is still clinging to the term Authorship. Why? Why is it so important to people? If anything, the authorship we see today is AI generated. Imagery is based on billions of images that were scraped. These common grounds, these images form the bedrock of generative image making – a form of cultural memory. To artists that are concerned about this, I can only say your art does not come out of nowhere. You were also influenced by the work of others. You were shown by a discriminator (your art professor) hundreds of examples that influenced your training. You know the work of poets, artists, thinkers, architects, who came before you that influence your work. So if I meet an artist who tells me that he basically invented his unique form of art – I’m not buying that. I think we are all influenced by our whole experience as a human condition. What AI does is basically mine the vast repositories of human creativity, which I think is incredible. So what I can do in my lifetime as a designer in terms of the articles I can read, the paintings I can see, the architectures that I can experience. It’s getting amplified enormously by using machine learning. So we can explore possibilities that we could not do previously in our whole lifetime. Now we can. However, that also means that we have to start to learn to share the authorship with the armies of artists, objects and ecologies present in the datasets. If we need to insist on having the term authorship, it needs to became an expression of communal efforts. The more I think about it, the more I’m convinced that this idea of the pyramid, where the human is on top of the artistic creation is very quickly eroding.

We have to start to think about it differently. Maybe it is not a pyramid, but rather a plateau – a plateau populated by a variety of different players, contributing to the creation of the piece of art. These can be humans, but can also be fauna, flora, geology, climatic and synthetic, like AI, right? James Bridle wrote this wonderful book, Ways of Being, where he lays out beautifully the various intelligences that exist on our planet alone. And who knows how many are out there. So this idea of human uniqueness, the humanist project, which, of course, supports ideas like authorship, is eroding and it might be a good thing that it’s doing that. It might help us to move forward on this planet in a more responsible way, because once you understand that you are not the dominating figure on the entire planet you might start to understand that you’re sharing this planet with others, and you have to take care a little bit more about it.

John Berger famously wrote about the gap between what we see and the words we use to describe such, in particular the passage “seeing comes before words. The child looks and recognizes before it can speak.”2 For you, “it is through language that we make meaning, and it is through meaning that we understand our place in the world.”3 This may be a linguistic brick wall; however, I am curious about this because it seems critical regarding the extrapolation of meaning from AI-generated output that relies on textual input.

This is a great question, one that resonates deeply with the ongoing linguistic paradigm shift we are currently witnessing, particularly within the realm of architecture. The convergence of AI tools with our creative processes has been a fascinating progression. Consider, if you will, the evolution of image generation models, which until recently predominantly relied upon text prompts for their operation. Then, the inception of combining images with language prompts marked a notable transition, allowing for a more nuanced synthesis of visual output. Yet, the most intriguing development lies in the refinement of blending tools. This advancement transcends mere juxtaposition, seamlessly blending multiple images to conceive novel, often unconventional compositions. Such innovation underscores the dynamic interplay between visual elements, fostering the emergence of previously unexplored aesthetic realms.

Now, onto the second facet of your question. A concept that encapsulates the essence of comprehension and tactile perception lives in the term begreifen. A term of profound significance in the German language. Its dual connotation, includes both tactile interaction and intellectual apprehension, and serves as a poignant metaphor for our cognitive processes. Just as touch enriches our understanding of physical objects, language serves as the conduit through which we grasp conceptual constructs. This symbiotic relationship between language and cognition gives rise to a peculiar ontological dilemma, wherein the act of linguistic description becomes intertwined with the essence of the object itself.

Consider this: when contemplating the outcomes provided by text-to-image generators, it is imperative to delve into the foundational underpinnings from which these manifestations emerge. The interplay between language and image engenders a fertile ground of ontological discourse, ripe for scholarly exploration. However, given the expansive nature of this discourse, a comprehensive interrogation of linguistic ontology warrants extensive scholarly engagement. Perhaps this is the work of a future Ph.D. student? Acknowledging the vast expanse of scholarly discourse surrounding linguistic ontology and its intersection with image generation, I shall refrain from further elaborating on this complex domain. Suffice to say, the complexities inherent within this discourse offer a rich hunting ground for intellectual exploration and scholarly inquiry.

I wonder about aspects of experiencing architecture that are difficult to explain in words, such as Marlon Blackwell’s crushed pecan shell floor covering in his Towerhouse project and the sound it creates when walked on; or John Hejduk’s strange architectural characters which almost emote in a way that is difficult to describe. The list goes on. Can an architecture generated by AI engage the non-visual senses?

Designing to evoke specific atmospheres poses a complex challenge, one that I find particularly intriguing. Image generators such as Midjourney, trained on datasets like the LAION 5B Aesthetics Dataset, exhibit a remarkable ability to produce imagery imbued with artistic essence, effectively translating visual atmospheres into tangible experiences. However, it’s important to recognize that while Midjourney excels as an ideation tool, it lacks the predictive and optimization capabilities found in other AI models.

It’s somewhat amusing to observe the proliferation of workshops and courses promising to teach individuals how to “Design with Midjourney!”—a notion that, in my view, oversimplifies the intricacies of architectural design and could be considered a deception, a con, a ruse. Drawing from our experiences at SPAN, particularly our involvement in the Deephouse project of 2022, we witnessed firsthand the significant degree of human intervention necessary to actualize architectural concepts derived from AI-generated imagery. The Deephouse project, while retaining elements of the ephemeral qualities you’ve mentioned, necessitated substantial human input to translate the AI- generated outputs into tangible architectural forms. Thus, designing with Midjourney, or any tool based on Diffusion models for that matter, requires a nuanced approach that integrates machine-generated inspiration with human creativity, highlighting the indispensable role of human ingenuity in the architectural process.

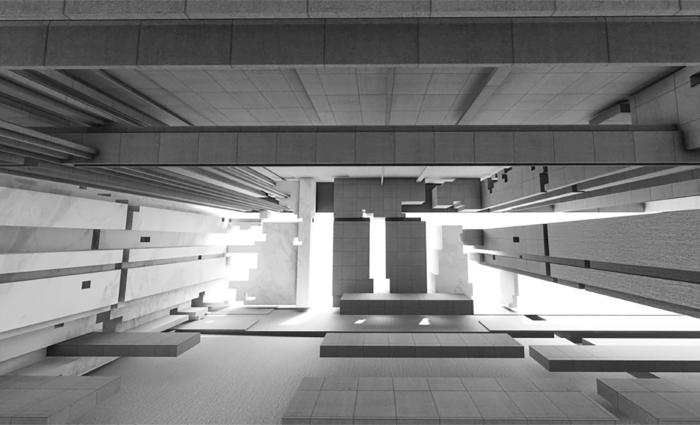

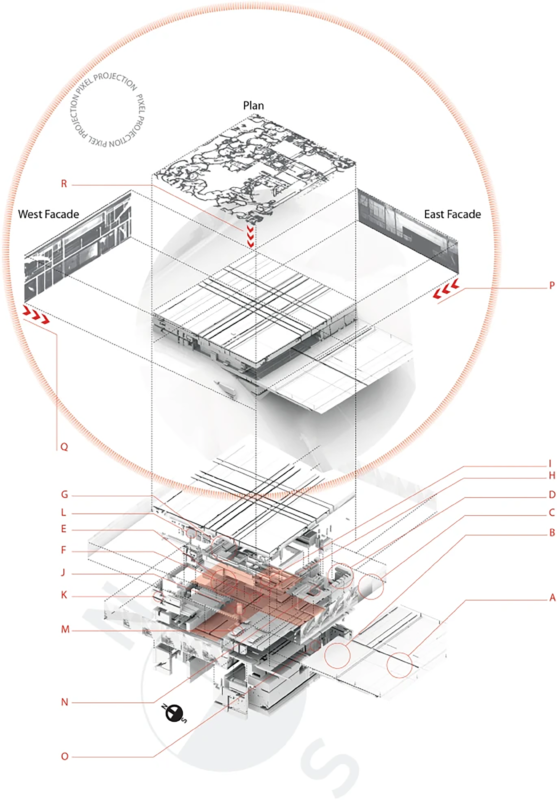

ABOVE: The Deephouse project uses a pixel projection technique to fold information present in 2D images resulting from a latent walk into 3D space. The pixel projection consists of three planes (x,y,z) used as the basis for three alpha channel images containing two facades and a plan resulting from the latent walks. The datasets of these latent walks consist of a midcentury modern house facade dataset and the respective plans. The training of these datasets was intentionally cut short in order to avoid realistic versions but rather to achieve estrangement effects.

BELOW: Master bedroom. SPAN, 2022.

Architecture is a complex subject to deal with, particularly as new technologies such as AI enter the discussion. You have described architectural design as having a “tame” and a “wicked” side.1

Tame and wicked problems are very common terms used in engineering. Simply put: a tamed problem is a reducible mathematical problem. For example, the measurements that you can take of an existing building, the numbers in your budget, the math of structural engineering and so on. Tamed problems are measurable, reducible. They’re pragmatic, rational, technocratic if you will. Wicked problems on the other hand, are things that are outside the realm of simple measurements. Does the space make me feel comfortable or suppressed? How do I respond to the materiality of the building? The warmth of the materiality, the exuberance of the space? Aspects that are outside the area of quantifiable measurement are what is called the wicked problem. Aesthetics, sensibility, and so on.

However, in a recent interview I made with Mario Klingemann, an exceptional German AI artist, he mentioned that AI has made possible to “measure the unmeasurable”. That is an astonishing insight, it means that the boundaries between the wicked and the tame are starting to blur – opening up exciting avenues!

You have posited that the arrival of AI has triggered an era of post-human design, where non-human agent(s) enter the design process. How does the architect, or artist for that matter, navigate such a relationship?

First and foremost, it’s important to clarify that when I refer to the “post-human,” I don’t mean a world without humans; rather, it signifies a departure from humans as the dominant force shaping our world. It involves letting go of the notion of human uniqueness, relinquishing the idea of human control over nature. In a post-human creative process, creativity no longer arises solely from individual minds; instead, it involves a multitude of participants. The conventional concept of the solitary genius is called into question here. Essentially, it’s recognizing that there’s a whole spectrum of contributors to the creative process, including humans, animals, natural elements, biological entities, plants, geological formations, and even synthetic elements. These various actors engage in a dynamic exchange of ideas, pushing and pulling together to explore new expressions of the human condition – or perhaps even beyond.

In Neural Architecture you highlight the pitfalls of generic datasets and the lack of such specific to architecture. Now that off-the-shelf image generators are available, are you still training your own neural networks?

Yes, we continue to develop our own datasets and train neural networks tailored to our specific architectural needs. The large-scale datasets utilized by diffusion models often lack the semantic information required to address architectural challenges comprehensively. Consider tasks like plan optimization, material usage analysis, ecological impact assessment, lifecycle evaluations, and construction management—these demand a depth of semantic understanding beyond what generalized datasets can offer. Expecting tools like Midjourney to provide such detailed architectural assessments is unrealistic, as they are not designed for such purposes.

To navigate the multifaceted realm of architecture—from conceptualization to construction, and throughout a building’s lifecycle – we require bespoke AI solutions. This is precisely the focus of my lab, the AR2IL lab at Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning, University of Michigan. Perhaps, rather than starting from scratch, AI can assist us in making informed decisions, guiding us towards responsible and ethically sound architectural practices while aesthetically representing the culture of the 21st century. In essence, leveraging AI in this manner would represent a triumph, balancing practicality, ethics, and aesthetics in architectural endeavors.

Neural Architecture as a design methodology is not only concerned with novel design pipelines and interrogations, as it also includes certain political leanings as well.

I’m truly enthusiastic about the evolution of architecture because it extends beyond mere technical and structural considerations. As you rightly pointed out, it encompasses broader aspects. Various contemporary design movements have attempted to intertwine architectural concepts with political ideologies, yet none have truly succeeded in my view. Specifically, Parametricism appears outdated both politically and technically, resembling a relic of the past. However, Neural Architecture introduces a new paradigm. It heavily relies on data, prompting us to scrutinize the ethics of data collection. This inherently raises political questions – such as whether data collection is equitable and whether individuals should be compensated for their data. We must also consider the diversity of the data we gather to ensure that our architectural solutions reflect a wide range of contexts and perspectives, rather than being biased towards specific regions or cultures. Discussing artificial intelligence inevitably leads us to confront issues of automation, which carry profound political implications. We’ve seen examples, such as James Bridle’s concept of “flesh algorithms,” where individuals are essentially reduced to facilitators executing algorithms in the physical realm, such as Uber drivers or Amazon warehouse workers. These workers become subject to control by algorithms, raising concerns about labor rights and the potential for unionization. Furthermore, as automation becomes more prevalent, we must question who benefits economically from this process. Does the wealth generated by automation accrue solely to a select few billionaires, or can we devise systems that distribute these benefits more equitably among society?

Several thinkers, including Nick Srnicek, delve into the political ramifications of this emerging landscape of AI and automation. Srnicek’s work on automation and politics offers valuable insights into these complex issues, provoking thought and discourse on how we navigate the intersection of technology, economics, and social justice.

Your latest publication Diffusions in Architecture: Artificial Intelligence and Image Generators3 records the arrival of text-to-image generators to the architecture scene, with examples by various practitioners and experts in the field. What impact do you hope this book will have, and how is it relevant to the profession today?

The book Diffusions in Architecture was conceived around the time when image generators first started to explode into the architecture scene in the summer of 2022. The idea was to capture the moment when a large-scale AI tool was available to a large number of architects for the first time. With an easy-to-use interface. What I was surprised about was that from the architects I invited to contribute, many opted to write extensively about their thoughts on this moment, denoting a paradigmatic shift. One of the hopes I have with the book is to create a vehicle for thinking through the problem of architecture and Artificial Intelligence. Not limited to AI models that are based on diffusion algorithms, of course, but rather generally speaking. How do you develop a language around this novel tool? I don’t mean just the visual language. I mean also literally writing about it, thinking about it, conceptualizing it, and intellectually interrogating the problem. That is why it was important not only to invite architects to this book, but also a series of theorists like Mario Carpo, Bart Lootsma, and Joy Knoblauch. I am very happy that Lev Manovich, wrote the preface, who I consider one of the most important and prolific thinkers when it comes to the impact of technology, to the arts.

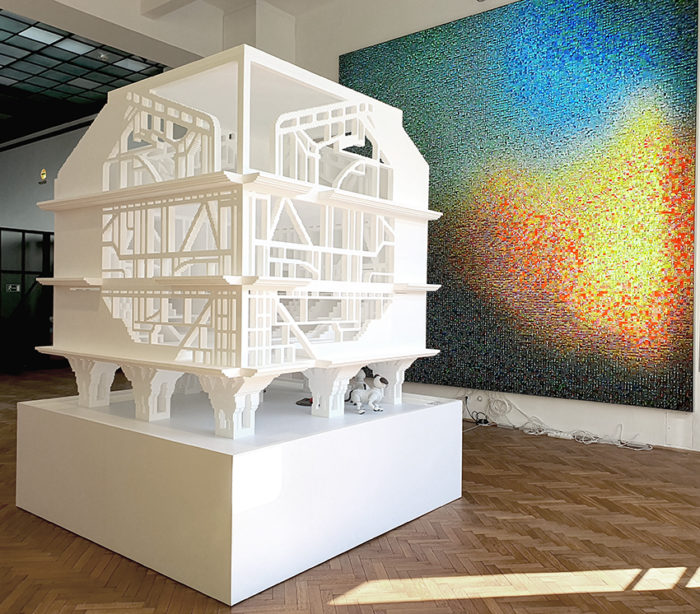

SPAN (Matias del Campo and Sandra Manninger) installed the Doghouse as part of the exhibition /Imagine – A Journey into the New Virtual at the MAK Vienna, 2023. This project is the first large scale prototype model that demonstrates the possibility to fold 2D images created with off-the-shelf Diffusion models such as Midjourney, DALL-E2 and Stable Diffusion into 3D objects.

I wonder if image generators aren’t simply furthering the idea of architecture as image, championed in part by the rendering revolution of the last couple of decades. Is it possible for a complex spatial understanding of architecture to be embedded in an AI-based process? I am thinking of places that are difficult to capture in images, such as the Piazza del Campo in Sienna or the complexity of spaces in historic cities such as San Gimignano, Aix-en-Provence or Florence.

If you think about it, we are basically talking about pixels. We are basically talking about two-dimensional surfaces. And there is the problem, once you fold 3-dimensional information into 2-dimensional surfaces, you will lose information in the process. The same, of course, happens when you are trying to unfold it from 2D to 3D. So there is always a loss of information going on. Which means that what you are discussing here, the difficulty to capture such things like the Piazza de Campo, Aix-en-Provence, San Gimignano, Florence, and so on in 2D will always come along with a loss of information. I think what you are trying to discuss here is whether I can capture the inherent atmospheric sensibility that exists in those spaces, and, to be honest, all the spaces you mentioned acquired this sensibility over time, not just because of the way they were planned. Now, what diffusion models do is they can capture atmosphere really well, right? They can contribute to the quality of the image, the ‘Gefühl’ of an image.

Things that we tried to achieve with rendering a decade ago which was really difficult to do, diffusion models can make in a really convincing and beautiful, aesthetically pleasing manner. Does that really help in translating that into a three-dimensional physical space? I am not so sure about that. There is, however, another way to see this.

Architecture has a tradition of translating concepts into a 2-dimensional surface in the form of a plan, a section, or an elevation, and then basically take that information and unfold it back as an object in the third dimension – in a far larger scale. That in itself, the Albertian paradigm, is an incredible intellectual achievement of the architecture discipline, which we can be proud of. If this is true, then it also means that creating plan sections and elevation in Midjourney, and then unfolding that into a three-dimensional space, has its merit. One of the projects that I can mention, which is a reference project for this idea, is the Dog House that Sandra and I showed last year in the MAK (Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna) show /imagine – a Journey into the New Virtual. For this installation, we created sections, elevations, and plans in Midjourney, and then used a pixel projection method in zBrush, to translate the pixels into 3D voxels. The goal was to create a physical 3-dimensional model. You could walk around, watch it, touch it, etc. And it was sizable. I mean, it was about 9’ by 9’ by 9’. This was just a proof-of-concept project, it

confirmed though that you can actually do that and build physical objects based on AI generated 2D information – this also means that you can encapsulate the properties you are asking for. Things like complex spatial features of architecture.

You wrote of how the last decade’s preoccupation with robotics and automation has left the discipline “blind in one eye.”1 Could you elaborate on what you meant by this?

I remember really well the fascination and obsession that started to emerge when the first examples emerged about using robots in architecture, which was around 2005, 2006. Kohler Gramazio installed the first robot at ETH Zurich to explore the possibility of using robots in construction. All the research went in that direction, right? At least a lot of it. The conferences presented in large parts projects trying to figure out how to create more and more exotic figurations, using robots. The thinking was akin to ‘if I use a robot, I can build anything’ It can be as complex as I want, and because it is automated, and because it is robotic, the price will be in par with a normal conventional construction. That was the thinking.

An enormous amount of time, effort, and energy was poured into that sort of research. I was part of that, and I am not excluding myself. I was part of the effort to understand how robots can be used in a variety of different fabrication methods, etc. But that sort of obsession obfuscated the layer of other elements that you can explore in terms of technology and architecture, one of them being Artificial Intelligence, which only in the last two years has started to somewhat seep into the architecture discipline. This whole obsession with robots and robotic fabrication left us blind in one eye – and in large parts it is a failure. Robots are still not a major factor in construction. I am looking for alternatives. I am looking for different ways in architecture. I am looking for understanding that the historic trajectories of our discipline can also show us the way into the future, which does not mean imitating old styles. It just means absorbing them better than we have done so far. Mining and extracting the large repositories of the history of our discipline, in order to enrich future designs.

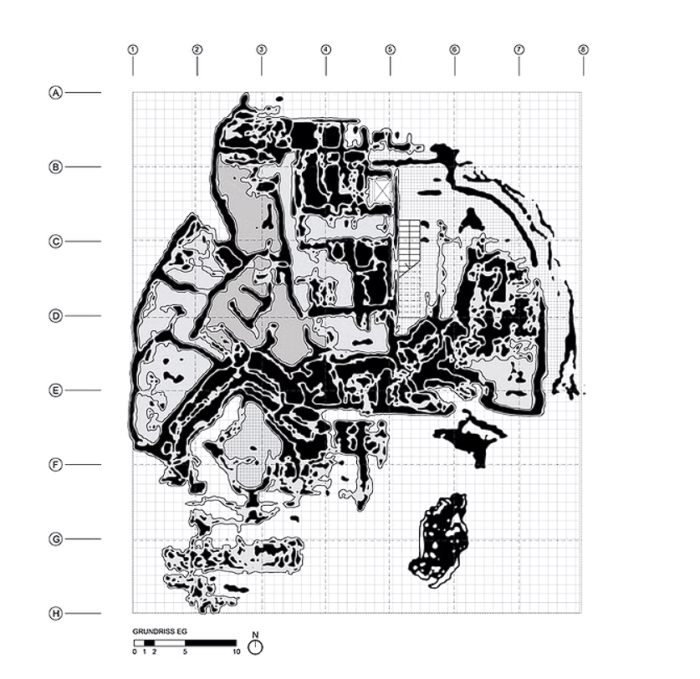

During the Summer of 2020, SPAN conducted a series of experiments interrogating the ability of GAN’s to combine features of Baroque and modern plans. The thick, voluptuous pochés, pleats and folds of the Baroque plan were successfully interpolated with the asymmetric features present in the modern plans.

In your early years you interned for Pritzker Prize winning architect and educator Hans Hollein. I am curious how that experience affected your current work, particularly your work with AI?

There is certainly one or the other thing that Hollein has affected in terms of my thinking about architecture. However, I am not sure it really affected my work about AI. I hope that these ideas, the concepts I have put on the table regarding the use of AI in architecture, are to some extent original. But then again, what is original anyways? What is originality today? Return to your question: there might be one or the other thing that really left an impression. Hollein’s insistence that everything can be architecture. ‘Alles ist Architektur,’ everything is architecture. When I was in high school I was lucky that I actually got the original publication of Alles ist Architektur in my hands, it was a magazine. It was called Bau. They were using those old magazines in my high school to give them to students to cut them up and make collages in art&crafts classes – imagine that! A couple of those magazines ‘fell in my backpack’. The examples in Alles ist Architektur – from race car engines to fashion design to pop art to space capsules and ascii art – absolutely astonished me! This somehow opened my mind to the possibility to see architecture less as compartmentalized and more like an open art form that allows us to digest and ingest enormous amounts of other things than what the common understanding of architecture is. The other aspect that greatly influenced me is Hollein’s affinity for art, his insistence that architecture is an art form. I share that sentiment that architecture is more than just creating a shelter. In Neural Architecture, I mention that ‘not every architecture is a building, and not every building is architecture.’

As the director for the AR2IL (the Laboratory for Architecture and Artificial Intelligence at the University of Michigan), what can new students expect when they enter the program?

The very first thing I try to convey to students is what I call demystifying artificial intelligence, meaning making them understand that it is a technology. It is not magic – they have a lot of influence on the results, because they basically create the datasets, manipulate the weights and tweak the algorithms. They define what kind of curve fitting they are trying to achieve in the latent space. The second part is the theoretical discourse. The implications that come along with them. How much it is going to change, how we think about architecture, how we conceive architecture? What is Posthuman Design? Posthuman Ecology? How do we question the project of human uniqueness? I love to have these debates with students discussing aspects of ethics, aesthetics, and politics of AI. These debates include the entire discourse around it, such as the history of AI, and the way it came into architecture. How it is changing the ontology of design, and the epistemology that the objects emerging from AI produce? We have the design studio, which focuses very much on how to apply these new tool sets successfully in design. There is a whole universe of possibilities that my students can explore within that. And I am also sure, by the way, that AI as a tool of architectural design is going to start to proliferate very quickly. It is after all the first design method of the 21st century. As it proliferates, more architecture educators will start creating their studios, seminars, and courses around AI. I’m sure it will not only be me teaching these ideas at Taubman College starting in the fall. Students can look forward to a whole ecology of possible design studios and seminars in the area of architecture and artificial intelligence.

Zack Saunders, the interviewer, is the founder of ARCH[or]studio and is a Contributing Editor for Arch2O.

REFERENCES:

1) Matias del Campo. Neural Architecture: Design and Artificial Intelligence. Applied Research & Design ORO Editions, 2022.

2) John Berger. Ways of Seeing. Penguin Books, 1972.

3) Matias del Campo. Diffusions in Architecture: Artificial Intelligence and Image Generators. Wiley, 2024.