ecoLogicStudio is an architecture and design innovation firm specialized in biotechnology for the built environment. Co-founded in London in 2005 by Claudia Pasquero and Marco Poletto, the studio has built a unique portfolio of biophilic sculptures, living architectures and blue-green masterplans. In 2018, it has joined the Synthetic Landscape Lab (University of Innsbruck; a unit focused on the application of recent scientific finding in MicroBiology and BioTechnology to the landscape) and the Urban Morphogenesis Lab (Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL; a unit focused on the application of recent scientific finding in Unconventional Computing to the Urban realm) to create the PhotoSynthetica™ venture. Together they are developing scalable, nature based design solutions to the imminent impact of climate change and to our contemporary quest for carbon neutrality.

We sit down with Claudia Pasquero and Marco Poletto to talk about their current and past work, a fresh look at Artificial Intelligence, and their new publication: Deep Green: Biodesign in the Age of Artificial Intelligence.

Many point to climate change as the reason that we need to rethink the built environment, as building and construction alone accounts for a large percentage of all global emissions, but they tend to stop there. Your work however showcases possible scenarios by which we might continue to build while combating climate change. Could you describe your design process? In particular, how might your approach differ from a typical architecture office?

We are a design innovation firm since we design spatially integrated biotechnological systems. The purpose is to reinvent the foundations of architecture, transforming the so called “machine for living” into a living architectural machine. It is a fundamental shift from the mechanical age where architecture was an instrument to control and frame nature towards a bio-digital age where architecture becomes an interface towards the living world. This transition is necessary if architecture is to become a true aid in the fight to mitigate the effects of climate change.

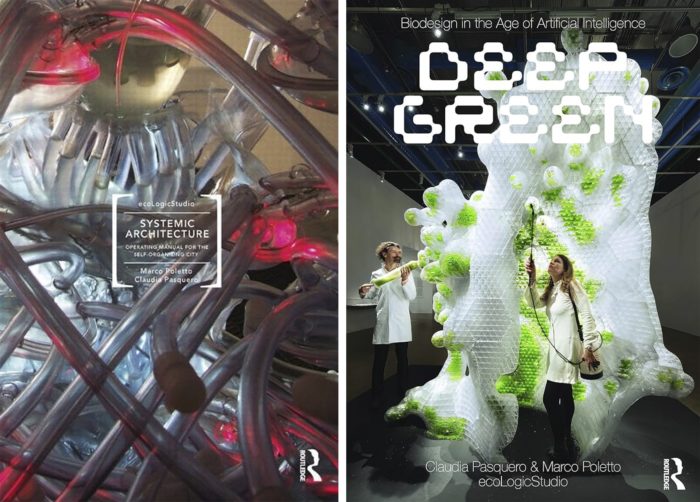

LEFT: Pasquero, Claudia and Poletto, Marco. Systemic Architecture: Operating Manual for the Self-Organizing City. Routledge, 2012. RIGHT: Pasquero, C. and Poletto, M. Deep Green: Biodesign in the Age of Artificial Intelligence. Routledge, 2023.

Systemic Architecture (Routledge, 2012) was full of examples of algorithmic design, information flows and computational simulations which pointed to a new understanding of the urban realm as a self-organizing city. How has your work evolved since the publication of your first monograph?

We have now developed a fully engineered PhotoSynthetica™ architectural system that is scalable and has already been applied to more than 15 pilot projects and scenarios worldwide. They are now the leaders globally in delivering bio-digital architecture to a wide range of clients, from cultural institutions, to the corporate and public sectors.

Your most recent book entitled Deep Green: Biodesign in the Age of Artificial Intelligence (Routledge, 2023) is divided in two main parts: PhotoSynthetica™ and Deep Green. As you mentioned above, PhotoSynthetica™ proposes incorporating various microalgae cultures directly into the built environment, and the book showcases examples of prototypes your studio has developed in recent years. Why is algae relevant to architecture today?

Micro-organisms like algae are tiny, single-cell organisms, so you can effectively design a habitat for them to grow and perform their metabolic action. This gives greater freedom than with a tree, for example. With micro-algae you have more flexible, effective, immediate relief in very dense environments. That’s what we are trying to demonstrate and develop. We’ve designed reactors (the vessels where living cultures grow) that can be integrated within a façade or in an interior space, your home or office. We have delivered more than 15 successful projects so we are way past the prototyping phase and are ready to scale the architectural innovation worldwide. We can thus turn buildings into air purifying, active photosynthetic systems.

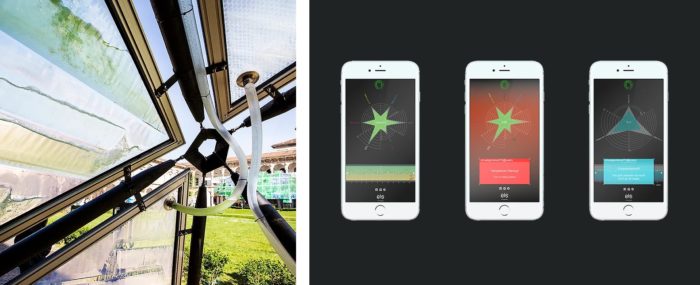

ecoLogicStudio, various implementations of PhotoSynthetica™, 2018 – present.

In the second part of your book, titled Deep Green, you describe your design and research methodology as a “Polycephalum,” a many-headed entity, which “attempts to develop an aesthetic language for architecture beyond such positivistic dualisms (as) form versus function and aesthetic versus ethic.” Could you expand on how your work attempts to transcend these dualities?

We often say that aesthetic and beauty is a measure of ecological intelligence. This is obvious when we look at many living organisms, like corals for instance, their aesthetic expression and beauty expressed a sophisticated survival logic evolved over millions of years and involved several symbiotic relationships. We are bringing this approach to architectural and product design.

Aesthetics is often associated with beauty, be it the appreciation or the understanding of it. Your definition of aesthetics, however, as a kind of “metalanguage” of nonverbal communication between human and non-human entities seems to differ greatly from the typical use of the word. What affected your concept of aesthetics, and how is does it inform your work?

We shall not confuse beauty with style. Stylistic disquisitions, so typical of architecture, do not interest us. This is because we look at architecture systemically and from this perspective aesthetics qualities serves a specific communication purpose across multiple systems. We are looking at the patterns that connect and correlate systems that operating perhaps across spatial and temporal scales, for example in the case of a living slime mold interacting and “designing” the new green network of a city.

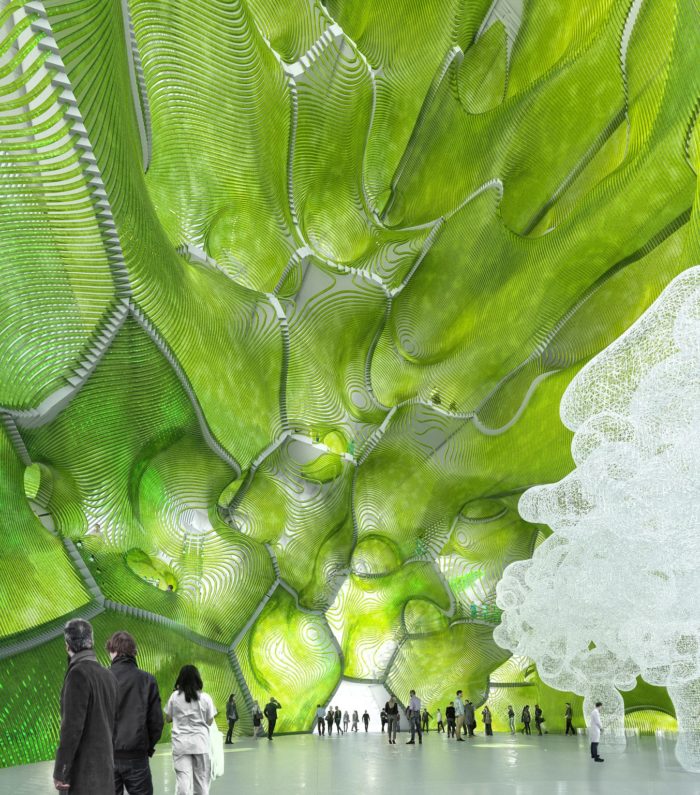

ecoLogicStudio in collaboration with the Synthetic Landscape Lab and CREATE Group/WASP Hub Denmark-University of Southern Denmark, H.O.R.T.U.S. XL Astaxanthin.g, Centre Pompidou, Paris, 2019.

Something that many in the design world get wrong, I think, is the derivation of form from organic precedents, while leaving behind the messy bits and forgetting the complex processes that drive organic form and are embedded in such. Your work tends to bring these organic qualities and processes to the forefront, resulting in a kind of hybrid between the synthetic and the natural. I am curious if you view your work in these terms, as hybrid, or are the natural components simply shored-up, so to speak, by synthetic means?

From an architectural and technological point of view, we think it’s totally possible to integrate some systemic logic back into our current building structure. The main obstacle we perceive at the moment is more the way in which production is conceived. One of the hallmarks of modernism has also been to segregate production from our living quarters and put it away from our sight and interactions as urban dwellers. But there could be a million other paradigms that take into consideration fungi, the non-human and bacteria that are usually associated with dirt and unhealthy conditions. These things actually have incredible properties that allow us to re-metabolize some of the pollution that we produce.

Scientists largely agree that we are now living in the Anthropocene, the latest stage of the Earth’s geological timescale which is marked by human intervention. As human activity impacts everything from the atmosphere to the Earth’s surface, a new concept of nature has been argued by philosophers and scientists alike, some even suggesting that nature no longer exists. Is a nature of the future only possible as one that is mediated by humans?

Today in the Anthropocene, biological systems are in one way or another technologically enhanced or mediated. Certainly, this is the case for humans, but most of the other systems we interact with have this kind of technological engagement, too. We’re trying to design this unavoidable convergence so that it can effectively benefit both human and non-human systems.

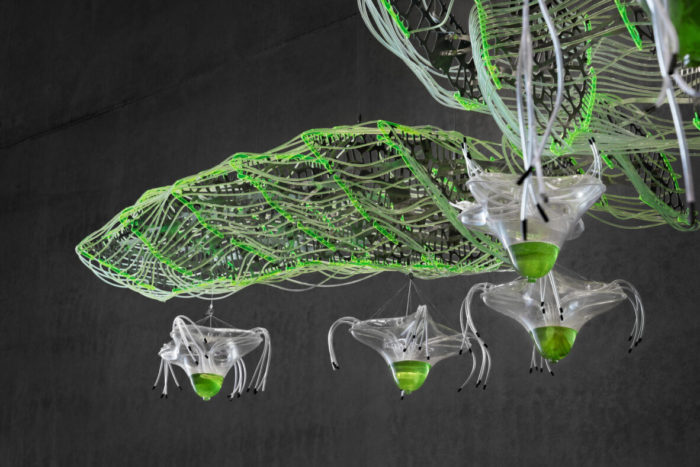

ecoLogicStudio, SuperTree. Presented at Futurium in Berlin, 2018.

How important is it that the spectator become a participant? I am thinking of the various arms of your PhotoSynthetica™ project, where the viewer is invited to pump or blow air into, or drink from, the architecture itself.

It’s a key point and one of our main challenges in scaling up. This is the question that clients have. They are interested in investing a bit more into integrating these green technologies with projects and taking a risk. But then, once this whole thing is up and running they ask: You know, who takes care of it? The maintenance is always the big issue. And typically in architecture, as in many other industries, the goal is to reduce maintenance almost to zero. Either through automation or through some other form of autonomous, self-caring system. As if by magic you don’t have to do anything. In a way we always try to challenge that. One of our original ideas was the concept of cyber gardening, an idea that takes gardening into the realm of architecture. Often mediated by digital technologies, but not exclusive to automation. This is about creating a new type of understanding of how digital intelligence, artificial intelligence, and biological intelligence, human and non-human actually begin to interact and begin to co-evolve. So the idea of cyber gardening was our way to try to turn the problem of maintenance upside down and say: “Hey, actually this is not a problem, is the key innovation.”

Artificial intelligence has arrived on the scene in the form of image generators, interior space layout iterators and even urban planning tools. These tools, however powerful, still rely mostly on input and instruction from the human operators. In Deep Green, you propose “a concept of artificial intelligence that is more like a slime mould, a spider’s web, a microalgae colony or a mycelium network.” How does this view differ from the popular notion of artificial intelligence, and how is it applicable to the built environment?

As many will know, the training of algorithms is a crucial component of AI, which involves multiple systems as part of the training apparatus, including humans. AI is largely trained and developed in a lab condition to perform tasks that revolve around how we can extract data or resources from environmental systems, animal or human systems. For example in the pig farming industry in China, AI is trained to enable incredibly dense, compact farming systems where millions of pigs are grown in artificial environments with their health and behaviour constantly monitored and optimized.

The only way that AI or similar technologies are going to become a force toward a sustainable, carbon-neutral world is if they are taught to understand ecological systems. At the moment, as with the pig farm example, we are using AI like the mechanical machines of the first industrial revolution. The material components might be different, but the cultural framing is the same. I believe that there is both an opportunity and urgency for architects, designers, and artists to challenge this. I see it as the factor which will most heavily affect the impact that AI will have on the future, and whether it will be a positive or negative impact on our own civilization.

What’s next for ecoLogicStudio?

We are now working on three products that we will launch in March 2024. It’s the first collection of products for the living environment designed by ecoLogicStudio and includes a desktop biotechnological air purifier, a compostable stool and bio-digital jewelry.

Alongside with the PhotoSynthetica Collection, we are working on a new outpost for ecoLogicstudio in the city of Turin perched inside the Ex Mulini Feyles, a 1910s industrial building in the city center. The Design Apothecary will showcase biomaterials, photosynthetic tools, living algae and products. It will be a 24/7 open biodesign laboratory, able to grow and craft new materials, products and practices to actualize a future concept of domestic environment. In the pipeline we also have a new book and a new iteration of the Air Bubble project.

ecoLogicStudio, PhotoSynthetica Collection. Photographs © Pepe Fotografia. 2024.

Zack Saunders, the interviewer, is the founder of ARCH[or]studio and is a Contributing Editor for Arch2O.