How Japanese Wood Joints Work Without Nails: The Ancient Art of Kigumi in Modern Architecture

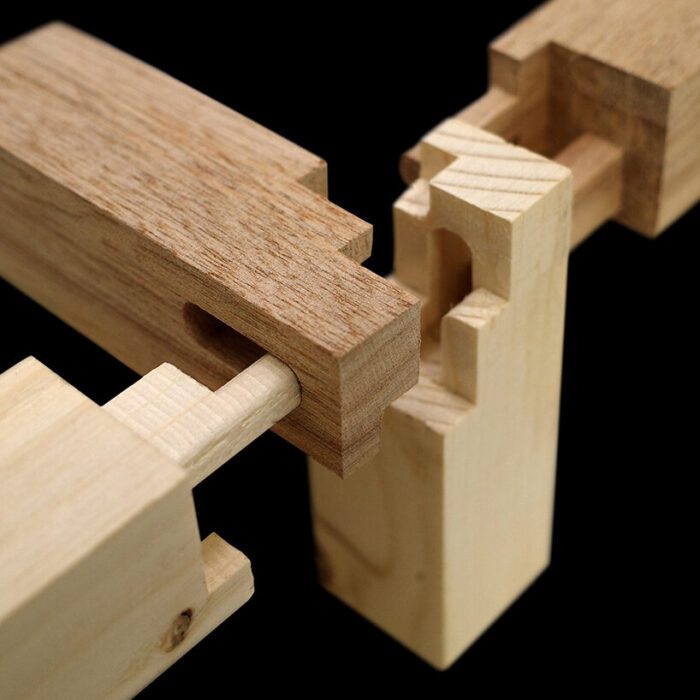

A master craftsman sits cross-legged on a workshop floor, shaving wood curls with a plane so sharp it could split a hair. No nails. No screws. No metal fasteners of any kind. Yet the structure he’s building will outlast skyscrapers made with steel and concrete.

This isn’t some romantic fantasy about old-world craftsmanship. It’s the reality of Japanese wood joints, where physics meets artistry in ways that challenge everything we think we know about construction. The principles behind this ancient craft are reshaping wood construction today, offering solutions to problems our industry didn’t even know it had. When you understand how these joints work, you’ll see why sustainable wood buildings are borrowing from techniques that predate the Roman Empire.

The Engineering Paradigm: Understanding Tsugite and Shiguchi Systems

Japanese joinery isn’t just carpentry—it’s applied physics disguised as woodworking. The whole system rests on two foundation concepts that sound simple but hide incredible complexity.

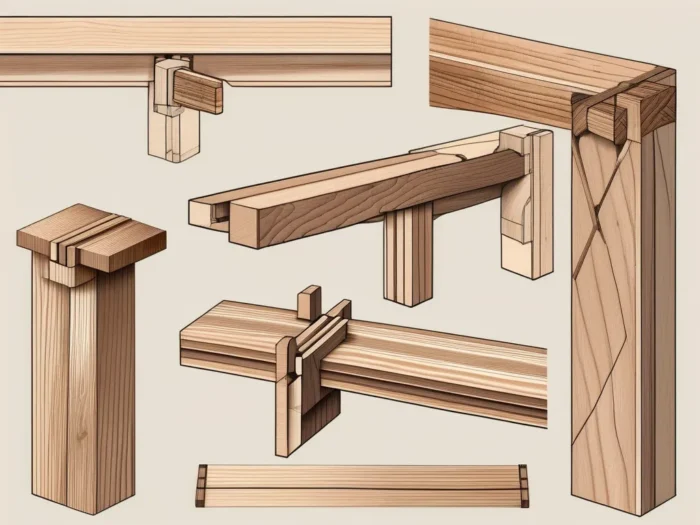

Tsugite: The Art of End-to-End Connection

Tsugite handles the challenge of connecting timber pieces end-to-end. Think of it as creating a continuous beam from shorter pieces, but without the weakness that comes from metal plates or bolts. The Japanese solved this by creating geometric locks that actually get stronger under load.

The precision required makes modern CNC machines look clumsy. Traditional craftsmen work to tolerances of 0.1-0.2mm using hand tools that have barely changed in centuries. That’s tighter than what most factories achieve today.

Shiguchi: Right-Angle Mastery

Shiguchi deals with connecting timbers at right angles—posts to beams, beams to braces. Here’s where the real magic happens. Instead of driving a nail through both pieces and hoping it holds, Japanese carpenters create three-dimensional puzzles where the wood itself becomes the fastener.

The load transfer in these joints follows paths that engineers are still studying. Forces spread through multiple contact points, distributing stress across the grain in ways that maximize wood’s natural strength while avoiding its weak points.

How Do Japanese Wood Joints Work Without Nails?

The secret lies in understanding wood as a material, not just a building component. Metal fasteners fight against wood’s natural behavior. Japanese joints work with it.

Geometric Interlocking

Imagine trying to pull apart two pieces of a jigsaw puzzle. That’s the basic principle, but Japanese carpenters take it further. They create joints that lock in multiple directions simultaneously. The famous kanawa-tsugi joint resembles a metal ring, but it’s carved entirely from wood. When assembled, it creates a connection that’s stronger than the original timber.

Compression Preloading

Here’s where physics gets interesting. Many Japanese joints use tapered geometry—a slight wedge shape that creates progressive compression as the joint seats. The more load you apply, the tighter the joint becomes. It’s like having a fastener that automatically adjusts its grip based on the forces acting on it.

A properly cut mortise-and-tenon joint in Japanese oak can withstand over 2,400 newtons of lateral force before failure. That’s comparable to modern steel brackets, but the wooden joint can be disassembled and reassembled indefinitely without losing strength.

Working with Wood Movement

Wood moves. It swells when wet, shrinks when dry, and changes dimension with temperature. Metal fasteners create rigid connection points that fight this movement, leading to splits and failures. Japanese joints anticipate and accommodate this behavior through calculated clearances and geometric design.

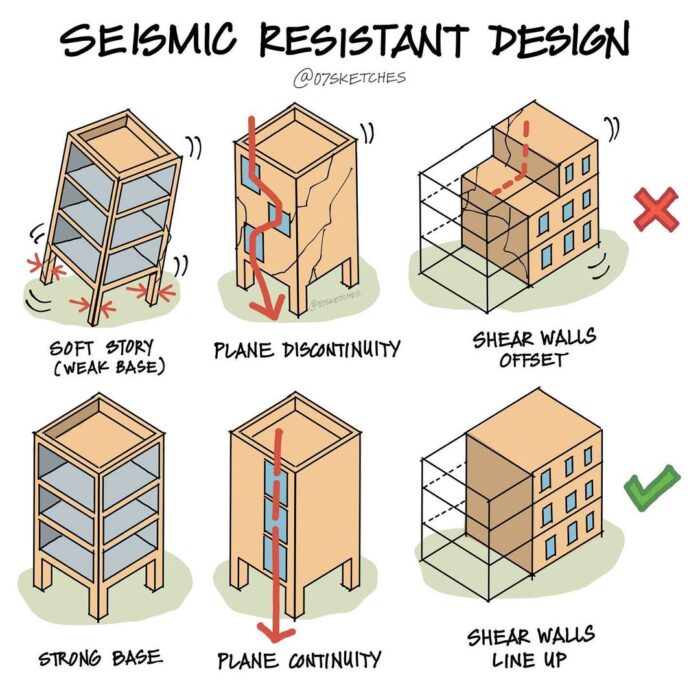

The joints in pagoda construction include deliberate gaps—typically 2-5mm—that allow controlled movement during earthquakes. The building flexes but doesn’t break, a principle that’s now influencing modern seismic design.

What Makes Japanese Joinery Different from Western Carpentry?

The difference runs deeper than technique. It’s a completely different philosophy about how buildings should work.

Reversible vs. Permanent Assembly

Western carpentry aims for permanent connections. You drive a nail, it stays driven. Japanese carpenters design for disassembly. Every joint can be taken apart without damage, allowing repairs, modifications, or complete relocation of structures.

This isn’t just theoretical. Traditional Japanese buildings were routinely disassembled and moved when families relocated. The joints made it possible to pack up an entire house and rebuild it elsewhere.

Distributed vs. Concentrated Loading

Metal fasteners create point loads—all the stress concentrates at the bolt hole or nail penetration. This reduces the effective cross-section of the timber and creates failure points. Japanese joints distribute loads across large bearing surfaces, using the full strength of the wood.

The dovetail joint shows this principle clearly. Its trapezoidal profile spreads loads across the entire width of the connection. The 1:7 slope ratio creates mechanical advantage—the harder you pull, the more the joint resists separation.

Material Understanding

Japanese carpenters see wood as an anisotropic material—one that has different properties in different directions. They design joints that align with wood’s strongest grain orientation while accommodating its natural movement patterns.

This knowledge influences everything from wood species selection to joint orientation. The result is structures that actually improve with age as the wood stabilizes and the joints seat fully.

How Long Do Japanese Wood Joints Last?

The proof is in the buildings. Some Japanese wooden structures have stood for over 1,400 years. That’s not just surviving—it’s thriving.

The Horyuji Temple Example

Built in 607 CE, the pagoda at Horyuji Temple represents the ultimate stress test for wooden construction. Recent structural analysis shows that the building’s joints have actually strengthened over time. The wood has reached equilibrium moisture content, and the joints have fully seated, creating tighter connections than when originally built.

The temple survived the 1995 Kobe earthquake, which registered 6.9 on the Richter scale. Modern reinforced concrete buildings collapsed, but the wooden pagoda swayed and settled back into position.

Self-Improving Connections

Japanese joints exhibit what materials scientists call “controlled stress redistribution.” As the wood ages and stabilizes, the joints gradually seat deeper. This creates a feedback loop where time improves performance rather than degrading it.

Metal fasteners work in reverse. They create fixed stress points that concentrate loads and accelerate wood failure around connection points. The older the building, the weaker these connections become.

Hygrothermal Stability

The joint designs incorporate controlled moisture movement. Traditional buildings “breathe” with seasonal changes, preventing the cyclical stress that causes conventional connections to fail. The joints accommodate this movement without compromising structural integrity.

How Are Japanese Temples Built Without Nails?

Temple construction without nails represents the pinnacle of Japanese joinery. These aren’t simple buildings—they’re complex structural systems designed to withstand centuries of earthquakes, typhoons, and human use.

The Assembly Sequence

Everything starts with timber selection. Species, grain orientation, moisture content, and specific gravity all influence joint performance. The wood is often air-dried for years before use, allowing it to reach stable dimensions.

Assembly follows precise protocols developed through centuries of trial and error. Primary structural elements connect through box joints that create rigid connections between posts and beams. Secondary elements use scarf joints that allow controlled movement.

Three-Dimensional Joint Systems

The famous “sunrise joint” used in temple construction achieves its strength through complex three-dimensional geometry. The joint locks under compression while permitting controlled expansion—a mechanical system that responds to changing loads and environmental conditions.

Modern analysis reveals sophisticated load path engineering. Forces transfer from roof loads through beam-to-column connections, then through foundation connections to ground. Each joint uses different geometric principles optimized for specific loading conditions.

Seismic Engineering

Japanese temples are earthquake-resistant by design. The joints allow controlled movement during seismic events, dissipating energy through friction and geometric compliance. The buildings flex rather than break, returning to their original position after the shaking stops.

This principle is now influencing contemporary seismic design. Modern buildings use base isolators and dampers to achieve what Japanese carpenters accomplished with wood joints centuries ago.

Modern Applications: Integrating Traditional Techniques with Contemporary Technology

The principles of Japanese joinery are finding new life in contemporary architecture. As the industry grapples with sustainability requirements and circular economy principles, reversible connections become increasingly valuable.

Digital Fabrication Meets Ancient Wisdom

CNC routing with 5-axis capability can achieve the precise tolerances required for effective Japanese joints. This marriage of ancient engineering with modern manufacturing opens new possibilities for sustainable construction.

The Japanese Pavilion at Expo 2000 demonstrated this fusion perfectly. Traditional joinery principles created a temporary structure designed for complete disassembly and reuse—a circular economy approach to construction that’s now standard practice in sustainable design.

Economic Advantages

While initial construction costs may exceed conventional methods by 15-20%, the elimination of metal fasteners reduces maintenance requirements and extends structural lifespan by factors of 3-5. The joints don’t corrode, loosen, or fatigue like metal connections.

This economic analysis becomes compelling when you consider the full lifecycle costs. A building designed for disassembly retains material value at end-of-life, while conventional construction typically ends in landfills.

Integration with Modern Materials

Japanese joinery principles are being adapted for modern materials and construction methods. The concepts apply to everything from wooden boards selection to wooden floor layout patterns that prioritize longevity over convenience.

Even the hardwood flooring dilemma between engineered and solid wood can benefit from traditional joinery principles. Understanding how wood moves and how to accommodate that movement leads to better design decisions.

The Science Behind the Craft

Modern engineering analysis reveals why these ancient techniques work so well. The geometry isn’t arbitrary—it’s optimized through centuries of empirical testing.

Finite Element Analysis

Computer modeling of traditional Japanese joints reveals sophisticated stress distribution patterns that optimize wood’s natural properties. The mortise-and-tenon joint’s geometry creates what engineers call “favorable stress fields”—compression zones that align with wood’s maximum strength orientation.

The wedge angles in traditional joints follow mathematical relationships that modern engineers express as optimization functions. The dovetail’s 1:7 slope ratio represents the optimal balance between mechanical advantage and bearing stress.

Stress Distribution Patterns

Digital strain measurement shows that traditional joints achieve stress distributions superior to bolted connections. The gradual load transfer through bearing surfaces eliminates stress concentrations that cause premature failure in metal-connected assemblies.

This finding validates centuries of empirical development and suggests broader applications for traditional principles in contemporary construction.

Future Implications

The integration of Japanese joinery principles into contemporary architecture represents more than nostalgic revival. It offers practical solutions to current construction challenges that our industry desperately needs.

Robotics and AI

Emerging technologies are beginning to decode the tacit knowledge embedded in traditional craftsmanship. Machine learning algorithms trained on master carpenters’ techniques can guide automated cutting systems to achieve traditional joint geometries with unprecedented precision.

This democratizes access to sophisticated joinery techniques while preserving their essential engineering principles. Soon, the precision of master craftsmen will be available to any builder with access to digital fabrication tools.

Circular Economy Applications

As building codes evolve to address climate change, the ability to disassemble and reuse structures becomes increasingly valuable. Japanese joinery principles offer a proven path toward zero-waste construction.

Projects like the cabins in the woods transformed into hotels show how traditional building techniques can create structures that adapt to changing uses without generating waste.

The ancient art of kigumi continues to evolve, its principles finding new expression in contemporary architecture while maintaining the essential engineering wisdom that has proven itself across centuries. In our quest for sustainable construction, we’re discovering that the most advanced solutions often draw from the deepest wells of human knowledge.

These aren’t just pretty joints or nostalgic references to a simpler time. They’re engineering solutions that solve real problems our industry faces today. The precision that comes from understanding materials, the durability that comes from working with natural forces rather than against them, and the sustainability that comes from designing for disassembly—these are the gifts that Japanese joinery offers to contemporary architecture.

The next time you see a building held together with nothing but wood and ingenuity, remember: you’re looking at technology that’s both ancient and futuristic, simple and sophisticated, traditional and revolutionary. That’s the paradox of Japanese wood joints—they’re everything our industry needs, hidden in plain sight.

Tags: apanese wood jointsJapanese carpentrykigumimortise and tenonnail-free constructionStructural EngineeringSustainable ArchitectureTraditional building techniquestraditional joinerywood construction

Emily Reyes is a Brooklyn-based architecture writer and Article Curator at Arch2O, known for her sharp eye for experimental design and critical theory. A graduate of the Southern California Institute of Architecture (SCI-Arc), Emily’s early work explored speculative urbanism and the boundaries between digital form and physical space. After a few years in Los Angeles working with boutique studios on concept-driven installations, she pivoted toward editorial work, drawn by the need to contextualize and critique the fast-evolving architectural discourse. At Arch2O, she curates articles that dissect emerging technologies, post-anthropocentric design, and contemporary spatial politics. Emily also lectures occasionally and contributes essays to independent design journals across North America.