“Wanted-1st, a story below-ground, containing boilers, engines of various sorts, etc.,-in short, the plant for power, heating, lighting, etc. 2nd, a ground floor, so called, devoted to stores, banks, or other establishments requiring large area, ample spacing, ample light, and great freedom of access. 3rd, a second story readily accessible by stairways,-this space usually in large subdivisions, with corresponding liberality in structural spacing and expanse of glass and breadth of external openings. 4th, above this an indefinite number of stories of offices piled tier upon tier, one tier just like another tier, one office just like all the other offices,-an office being similar to a cell in a honey-comb, merely a compartment, nothing more. 5th and last, at the top of this pile is placed a space or story that, as related to the life and usefulness of the structure, is purely physiological in its nature,-namely, the attic. In this the circulatory system completes itself and makes its grand turn, ascending and descending. The space is filled with tanks, pipes, valves, sheaves, and mechanical et cetera that supplement and complement the force originating plant hidden below-ground in the cellar. Finally, or at the beginning rather, there must be on the ground floor a main aperture or entrance common to all the occupants or patrons of the building.”

– Louis Sullivan, “The Tall Office Building Artistically Considered”, 1896

More than one hundred years ago, Louis Sullivan wrote about the skyscraper and the requirements made of it by the business world and by the congestion culture of late-capitalism’s large cities. Above is a passage where he states, in a pragmatic way, what is required of a tall office building.

Exactly 99 years later, Rem Koolhas wrote about “Bigness, or on the problem of the large”. He stated that sheer size is, in itself, an ideological agenda; that beyond a certain size, Architecture follows another rule book. “Bigness” invented a whole other playing field, one where traditional Architectural considerations need not apply.

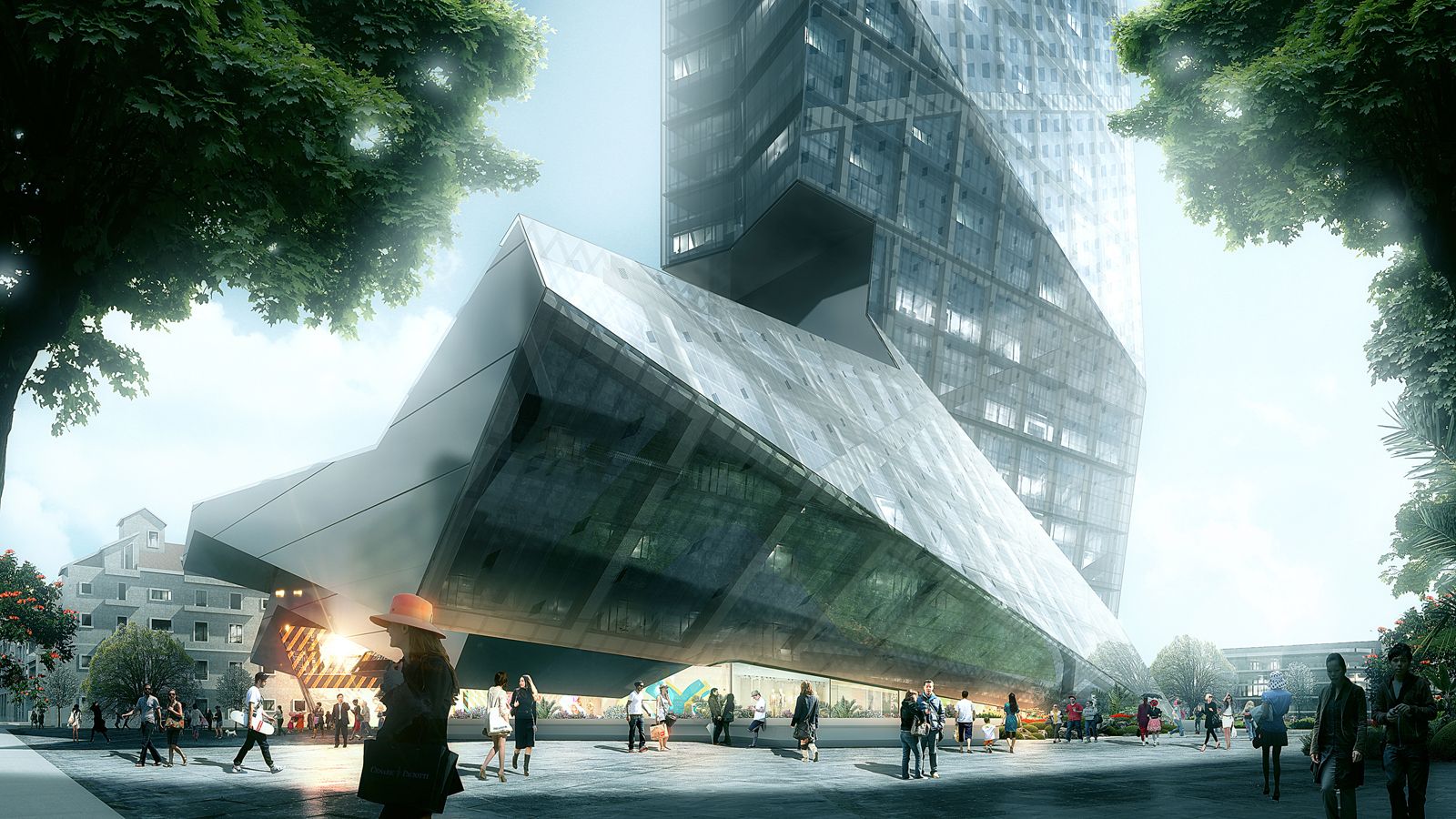

Enter the Hanking Center Tower. The year of the proposal is 2015, and this tower reflects and expands upon the centenary concept of the skyscraper. The feeling one has with this building is that it condenses both the concept of the skyscraper and the concept of the “Big” building. It’s bottom section, it’s atrium, functions as a sort of “Big” building in itself.

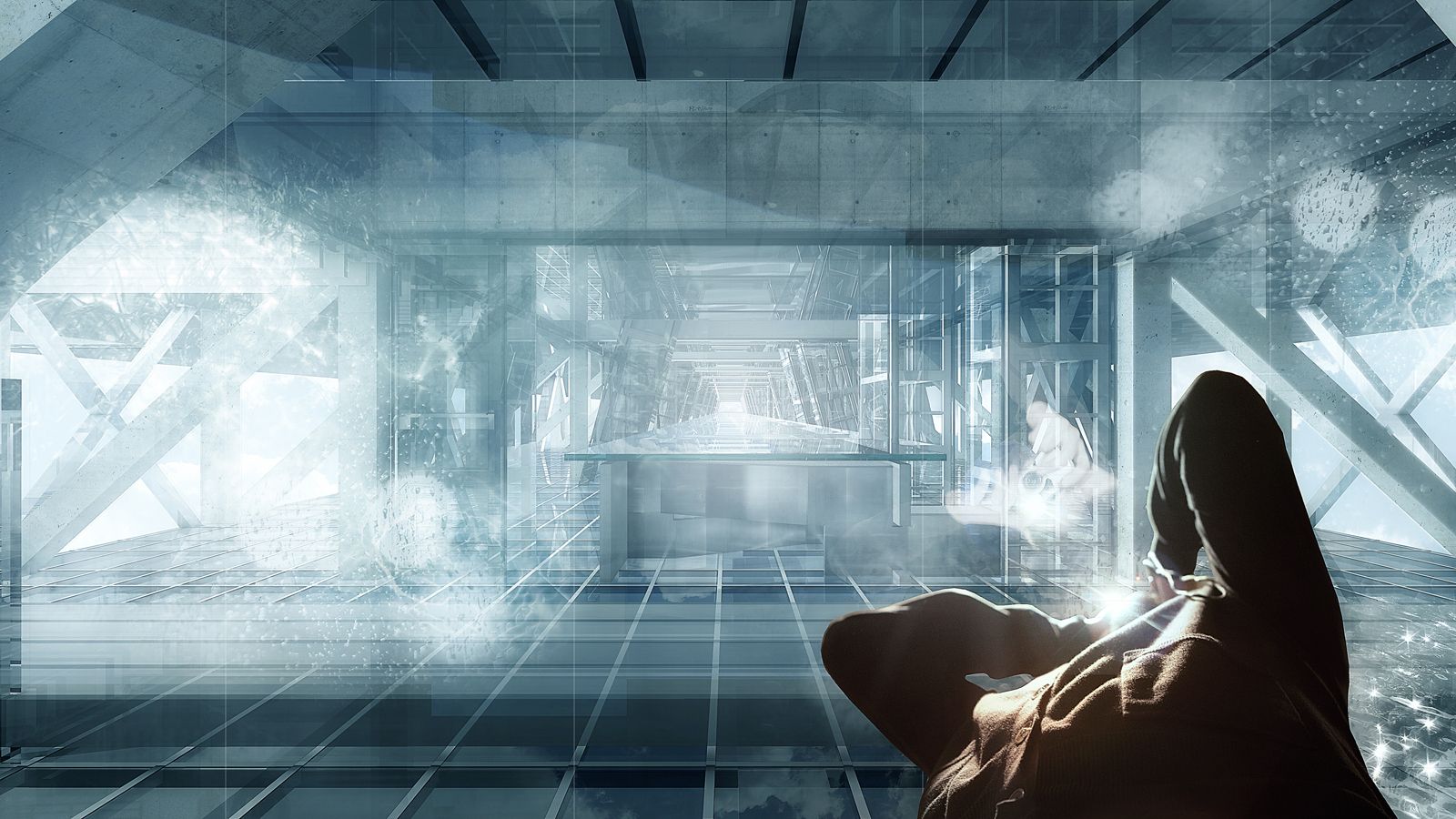

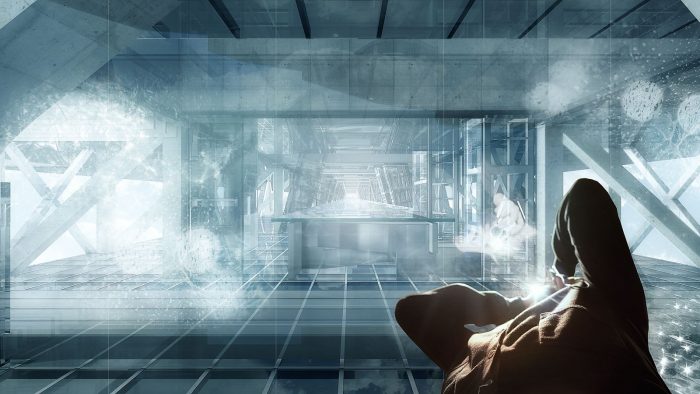

In Sullivan’s text, it is stated that the tall office building is required to have ample bottom floors, where freedom of access is key, and where one may find the most public functions harbored by the building. Morphosis Architects have provided this tower with a tremendously ample atrium – “Big”, as Koolhaas would say. Mighty concrete pillars and beams, walls and stairs punctuate this space, which is reminiscent of OMA’s “Casa da Música”, in Oporto.

One could characterize this building, then, by it’s attempt to cross the “Big” building – the atrium – with the skyscraper. And perhaps this is one of the reasons why the crooked geometry of the shapes works – its sheer size puts it in a whole other category of architecture, where its justification and presence is self-referential. The feeling of inferiority that some of these images ellicit on the observer is precisely what Frank Lloyd Wright disliked about the scale of buildings on cities like New York – he said Man was disrespected. The awe produced by these buildings in people came from a feeling of inferiority. In a sense, that is also true about Hanking Tower, twice – once because of it’s atrium’s “Bigness” and once for the fact that it is a skyscraper.

It’s a tall office building: what else could it be made of except for steel and glass? One of the practical demants made of a tall office building, as stated by Sullivan more than one hundred years ago, is that one repeats the floors destined for offices as much as possible, in order to maximize profit from a fixed plot of land. In this building, the core body of the tower is an extrusion of a perimeter that recedes into itself, creating open spaces between sections of the tower, connected at times by bridges like the one seen below.

Ultimately, one could deem this project to be a fine exercise on the possibilities of scale, made possible by the elevator, by modern building technologies and by the market logic of late-capitalist society, that requires such huge buildings to satisfy the demand for concentrated – congestioned – office spaces. In fact, this building efectively celebrates the idea of the culture of congestion.

There may be some who dislike this building, and they have every right to. They may deem it too “capitalist”, too “big”, too indifferent to it’s surroundings; or part of an inherently unequal system, that wastes the resources of our planet and squanders human potential for the profit of few. Perhaps that is true. But one thing that Morphosis cannot be accused of is incoherence. This piece of architecture is unapolageticly capitalist and it serves big business and corporate culture – and it shows, in a brutally honest way. Floor after floor, Architecture is surrendered to the demands of the contemporary world.

It’s a symptom of globalization; a palace for both progress and it’s inherent decay. And a beautiful one, at that.

Architects: Morphosis Architects

Location: Shenzhen, Guangdong, China

Design Director: Thom Mayne

Project Principal: Eui-Sung Yi

Project Manager: Hann-Shiuh Chen, Amit Upadhye

Project Architect: Mario Cipresso, Jamie Wu