Tokoname has continued to supply tsuchimono (earthenware) to the Japanese archipelago, flourishing on the heights overlooking Ise Bay. The term tsuchimono is intentionally used here instead of “ceramics” to emphasize that Tokoname’s Doma of Tokoname extended beyond daily utensils to include civil engineering components such as clay pipes and tiles. Tokoname takes pride in its deeper, more ubiquitous role in supporting everyday life across Japan—both visibly and behind the scenes.

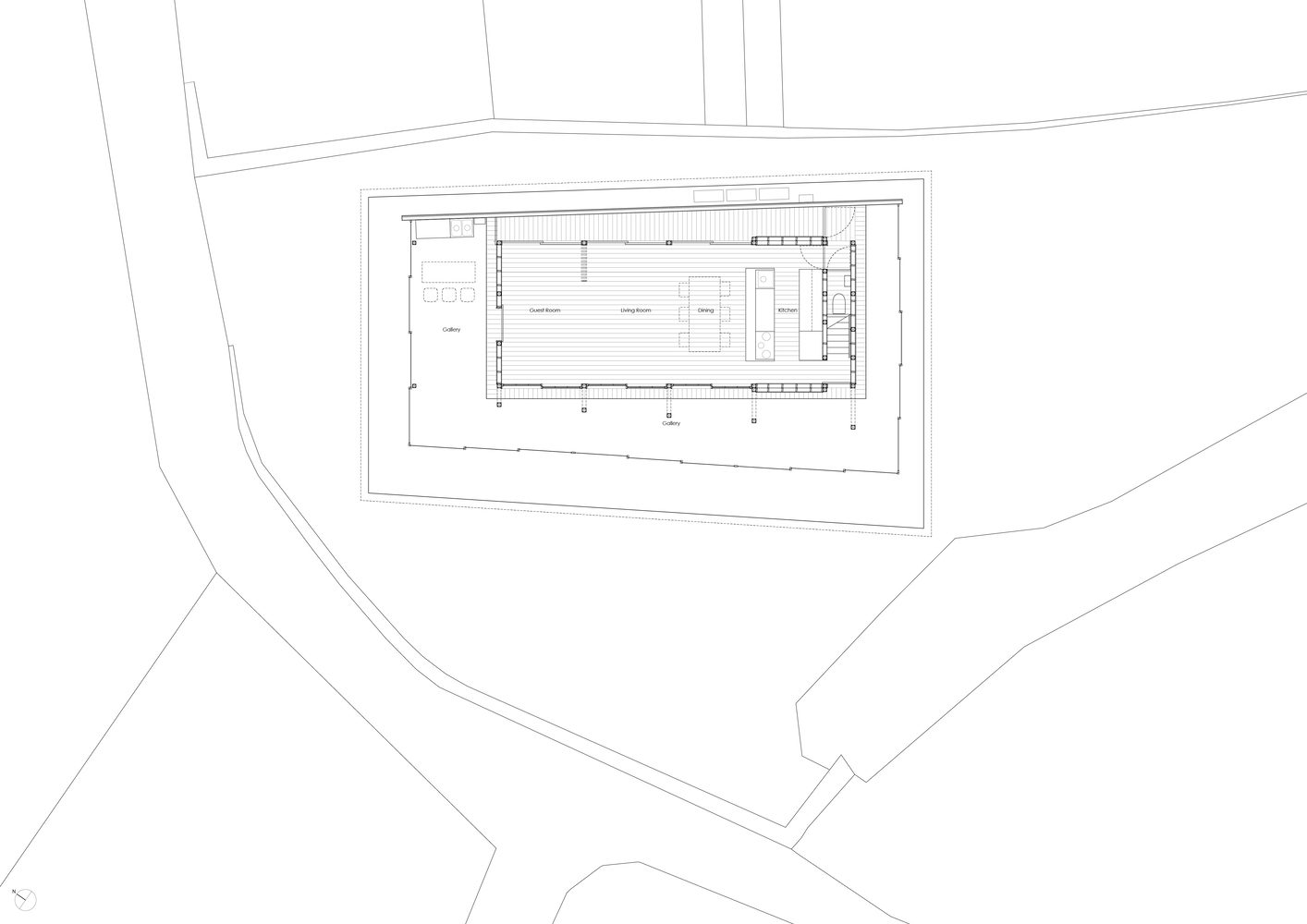

The site lies along the approach to Dokanzaka, Tokoname’s equivalent of Tokyo’s Ginza. Owing to the quirks of history, the ground is scattered with fragments of clay pipes and pottery. Buildings in this atmospheric area seem to take root by parting through layers of ceramic debris. Elegant townhouses are rare in Tokoname. Instead, it is the ordinary, blackened buildings—modest structures that have faithfully supported the livelihoods of residents—that cluster together and preserve the town’s character.

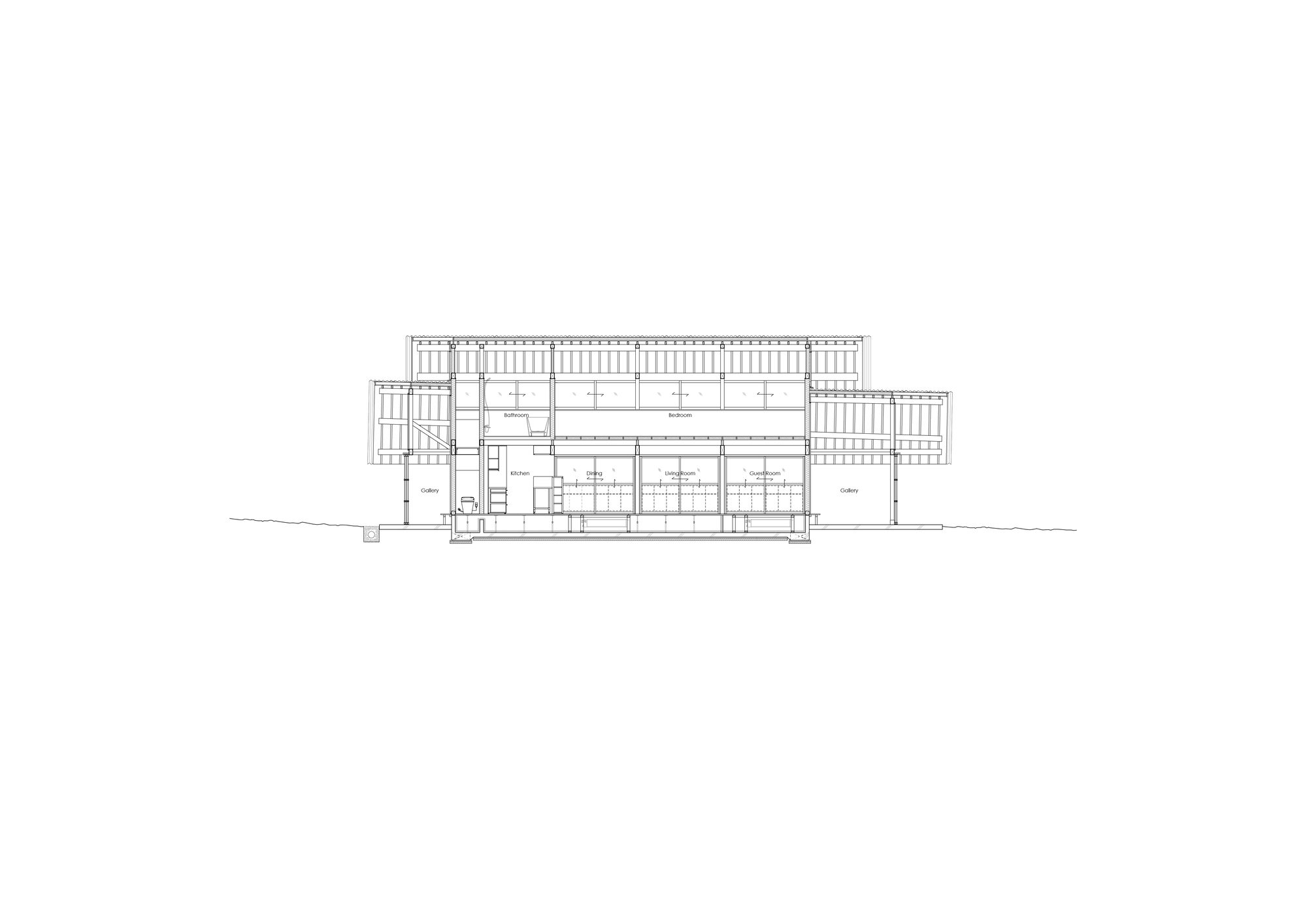

Doma*, as an earthen-floored space, surrounds the house. In this town of earthenware, shops selling pottery traditionally operate in the doma. Although the products are already kiln-fired and not susceptible to dirt, this layout has become customary. The shop space wraps around the building, taking advantage of the three open sides of the site that overlook Ise Bay.

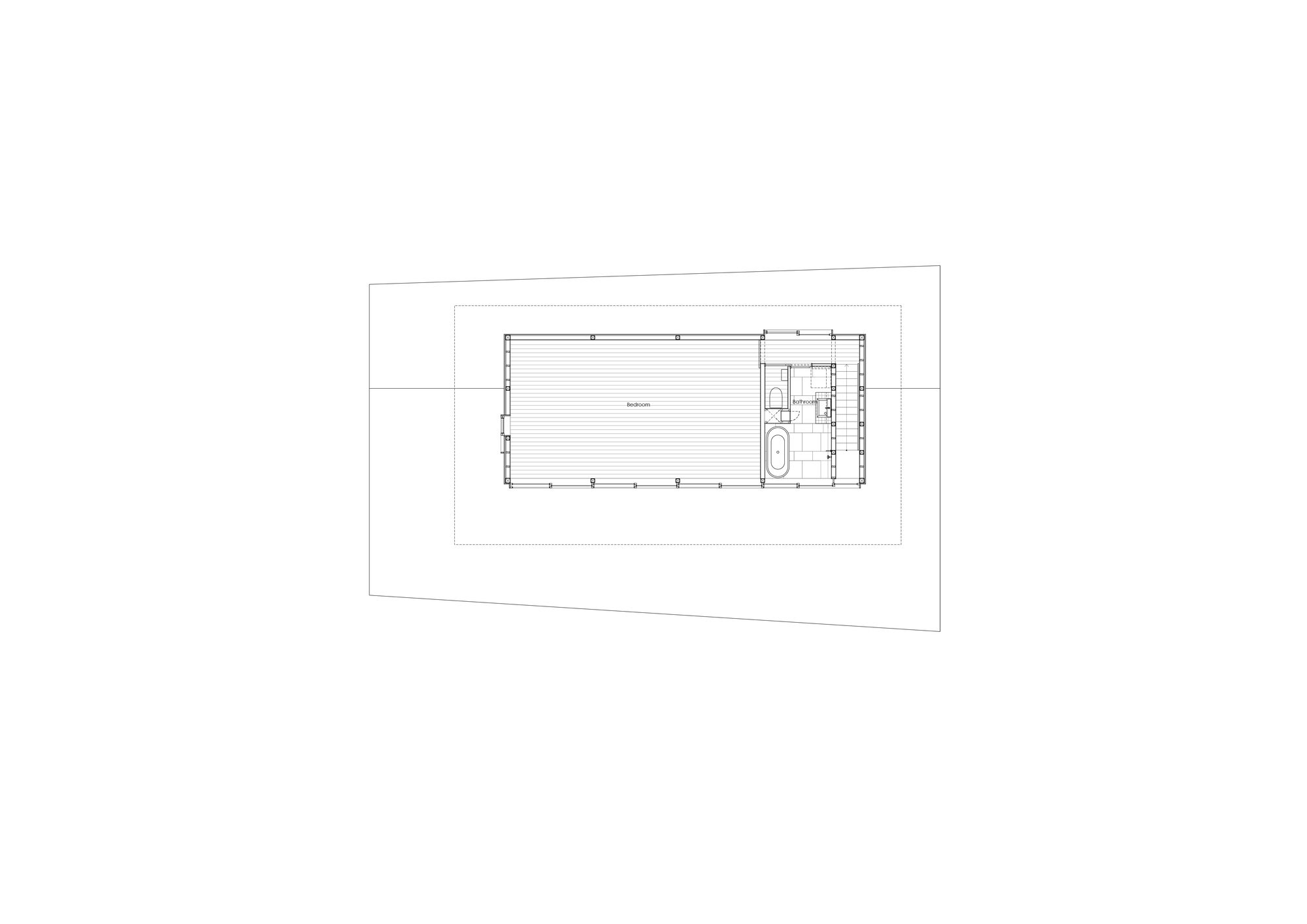

The building takes the form of a small house nestled within a larger one—like a yolk within an egg white. A shikidai (entry step) that also acts as a resting space leads from the doma up into the residence. Between the living quarters and the doma is a partition of reversed yukimi-shōji—sliding screens with glass upper panels instead of the traditional lower one. This is a thoughtful feature, allowing the residents to assist with shop duties while maintaining privacy. Since the residence is raised about 350 mm above the doma, the lower mago-shōji (inner shoji screen) can be lifted to about 1000 mm, effectively shielding the interior from view.

When the partitions are fully opened, the entire shop transforms into a vast semi-outdoor space, shaded by the roof. The eaves are deeply cantilevered, extending 4.7 meters from the main structure. In traditional wooden construction, hijiki (bracket arm) supports the projecting beams. Here, tail rafters hold the eave purlins, which are aligned with the eave beam. Though it may appear unusual, this is a textbook example of traditional Japanese timber construction. The illusion of uniqueness stems not from any novelty, but from the fact that such a structure appears in a private residence rather than a temple.

Given its location, there is no doubt that tourists mistaking it for a historical monument will stop to take photos. Yet in truth, it is nothing more—and nothing less—than one of the many humble homes standing side by side in this town.

*Doma is a traditional Japanese

earthen-floored space located at the threshold between indoors and outdoors. Yukimi Shoji is a traditional Japanese sliding screen with a translucent paper-covered frame and a lower glass section for viewing of snow garden while seated indoors.

Project Info:

-

Architects: Tezuka Architects

- Country: Tokoname, Japan

- Area: 176 m²

- Year: 2024

-

Photographs: Katsuhisa Kida / FOTOTECA

-

Lead Architects: Takaharu Tezuka, Yui Tezuka, Keiji Yabe

-

Structure Design: Ohno JAPAN, Hirofumi Ohno, Yue Zhou

-

Lighting Design: Bonbori Lighting Architect & Associates, Masahide Kakudate, Sachiho Kurokawa

-

Contractor: Hakoya co.,ltd., Shigeo Matsumoto

-

Category: Houses, Commercial Architecture

-

Project Architects: Jieqiong Gao

Sophie Tremblay is a Montreal-based architectural editor and designer with a focus on sustainable urban development. A McGill University architecture graduate, she began her career in adaptive reuse, blending modern design with historical structures. As a Project Editor at Arch2O, she curates stories that connect traditional practice with forward-thinking design. Her writing highlights architecture's role in community engagement and social impact. Sophie has contributed to Canadian Architect and continues to collaborate with local studios on community-driven projects throughout Quebec, maintaining a hands-on approach that informs both her design sensibility and editorial perspective.