Villa Savoye Problems: The Dark Side of Le Corbusier’s Modernist Masterpiece

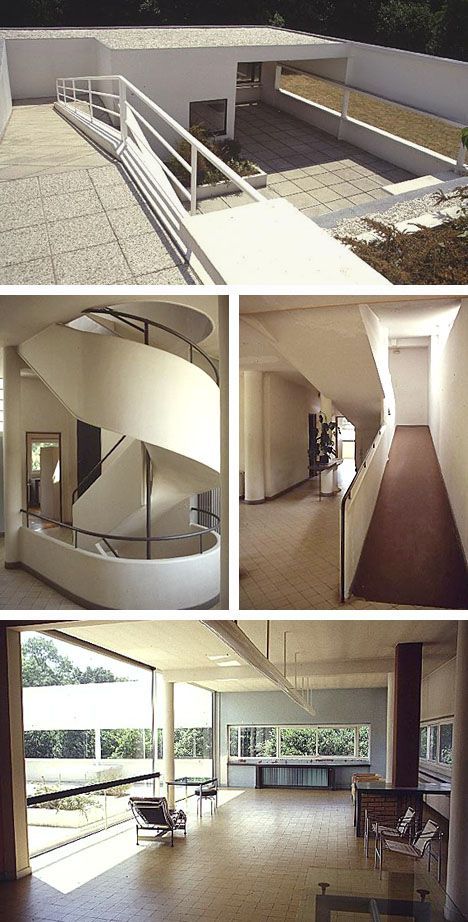

Villa Savoye stands as one of the most iconic buildings of modern architecture, a pristine white box that embodies the revolutionary vision of Le Corbusier and his cousin Pierre Jeanneret. Completed in 1931 in Poissy, just outside Paris, this country house for the Savoye family was meant to be a machine for living—a healthy, efficient, and beautiful sanctuary. You can even watch this illustrative video of Villa Savoye explaining Le Corbusier’s 5 Points of Architecture to see the theoretical brilliance behind the design.

But behind those famous pilotis and horizontal windows lies a story that rarely makes it into architecture textbooks. While the villa’s design principles revolutionized modern architecture and inspired countless replicas worldwide, the Savoye family themselves lived through a nightmare that nearly destroyed Le Corbusier’s reputation.

The Five Points That Changed Architecture

The villa’s fame rests on Le Corbusier’s ‘five points of modern architecture‘—a manifesto that would reshape the built environment:

-

Open plan that eliminates interior partitions

-

Pilotis—a reinforced concrete column grid that replaces load-bearing walls

-

Horizontal windows for even daylight distribution

-

Independent façade freeing the exterior from structural constraints

-

Roof gardens that protect the concrete roof while providing outdoor space

These principles look brilliant on paper. In practice, they created a perfect storm of building performance failures that left the Savoye family cold, wet, and furious.

The Hidden Nightmare: What Really Happened at Villa Savoye

The Leaks That Wouldn’t Stop

The problems began almost immediately. Rainwater found its way into the house through multiple points of failure—flat roof, skylights, and even the iconic ramp. Madame Savoye’s letters to Le Corbusier reveal the growing desperation:

“It is still raining in our garage,” she wrote, after complaining about a buzzing skylight that “makes terrible noise…which prevents us from sleeping during bad weather.”

The situation deteriorated rapidly. Another letter detailed the extent of the water infiltration: “It is raining in the hall, it’s raining on the ramp and the wall of the garage is absolutely soaked……It is still raining in my bathroom, which floods in bad weather, as the water comes in through the skylight. The gardener’s walls are also wet through.”

The final warning shot came when she wrote: “After innumerable demands, you have finally accepted that the house you built in 1929 is uninhabitable…Please render it inhabitable immediately. I sincerely hope that I will not have to take recourse to legal action.”

The Contractor Who Saw It Coming

Perhaps most damningly, the villa’s contractor had warned Le Corbusier during construction that the design would create future problems. The experimental flat roof lacked the slope and drainage systems that conventional pitched roofs provide. The extensive glazing, while architecturally stunning, created “substantial heat loss” and made the interior feel “moist and cold”—hardly the healthy living machine Le Corbusier had promised.

The Health Crisis

The architect had publicly declared that architecture should enhance one’s health, yet Madame Savoye’s health reportedly deteriorated while living in the house. The combination of damp conditions, poor heating, and thermal discomfort created an environment that was actively harmful. Time magazine captured the irony in 1935: “Through the great expanses that he favors may occasionally turn his rooms into hothouses, his flat roofs may leak and his plans may be wasteful of space, it was Architect Le Corbusier who in 1923 put the entire philosophy of modern architecture into a single sentence ‘A house is a machine to live in.

The Questionable Orientation

Adding to the technical failures, the villa’s orientation remains puzzling. The site was quite big, offering numerous better options for positioning the house to maximize solar gain and minimize weather exposure. The chosen orientation seemed to prioritize the visual composition from specific viewing angles over environmental performance—a common criticism of early modernist architecture that favored form over function.

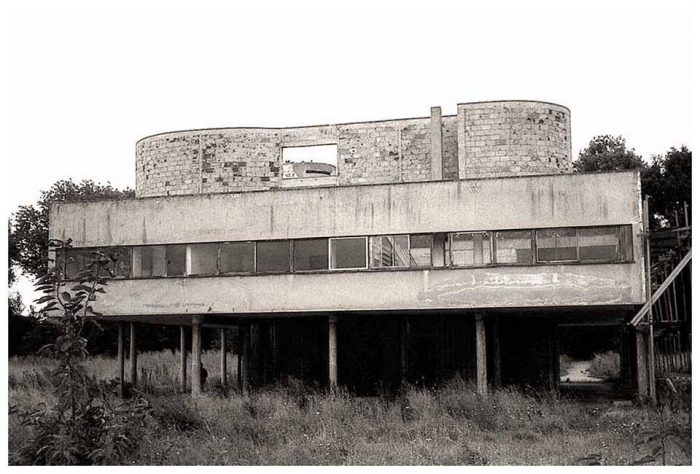

The Final Blow: WWII and Abandonment

As if the design flaws weren’t enough, German forces burglarized the villa during World War II, causing further damage that rendered it completely uninhabitable. The family faced an $80,000 renovation bill—equivalent to nearly $1.7 million today—and decided they’d had enough. They never returned.

Why Villa Savoye’s Failures Actually Matter

Here’s what makes this story fascinating rather than simply tragic: every one of these failures taught the architecture profession something invaluable. The leaking roof revealed the critical importance of proper drainage and waterproofing membranes. The thermal discomfort led to better understanding of building physics and insulation. The orientation issues sparked research into climate-responsive design.

Le Corbusier himself learned from these mistakes. His later projects incorporated more sophisticated detailing and environmental strategies. The villa became a living laboratory—its problems more influential than its successes.

Why does Villa Savoye have so many problems?

The issues stemmed from experimental construction techniques, immature building technology, and prioritizing aesthetic principles over proven performance. The flat roof lacked adequate slope and waterproofing for 1930s materials, while extensive glazing created thermal bridging and heat loss that early modernists didn’t fully understand.

Was Villa Savoye a complete failure?

Not at all. While it failed as a comfortable home, it succeeded spectacularly as a manifesto that transformed architectural thinking. Its influence on the International Style and modern design is immeasurable. The building’s problems actually accelerated improvements in building science and construction detailing.

Did Le Corbusier fix the issues at Villa Savoye?

Le Corbusier made some repairs during the 1930s, but the fundamental design flaws remained. The family abandoned the house before comprehensive solutions could be implemented. The building required three major renovations (1959, 1985-1997) to become the stable museum we see today.

Is Villa Savoye still worth visiting?

Absolutely. The villa is now a meticulously restored UNESCO World Heritage site. Architectural students from around the world pilgrimage there to experience the spatial qualities that photographs can’t capture. The building represents a pivotal moment when architecture broke from tradition and embraced modernity—flaws and all.

How much did it cost to repair Villa Savoye?

The 1997 restoration alone cost over $4 million. The cumulative renovation expenses across three major interventions have exceeded the original construction cost many times over—a testament to the building’s cultural importance despite its technical shortcomings.

The Unexpected Redemption

One might imagine such a faulty design would be thrown into oblivion. Instead, Villa Savoye made the list of public buildings in 1964 and has undergone three revamps, with the last major restoration completed in 1997. Today, it stands not as a cautionary tale of hubris, but as a honest monument to architectural experimentation—flaws, failures, and phenomenal influence included.

The building’s struggles humanize the legend of Le Corbusier. They remind us that every revolutionary idea goes through painful iterations, and that the buildings we admire in glossy photos often had difficult births. Villa Savoye’s dark side doesn’t diminish its importance; it makes its legacy more honest and more valuable.

Daniel Mercer is a Coffee Break section editor at Arch2O, currently based in Berlin, Germany. With a background in architectural history and design journalism, Daniel holds a Master’s degree from the University of Edinburgh, where he focused on modern architecture and urban theory. His editorial work blends academic depth with a strong grasp of contemporary design culture. Daniel has contributed to several respected architecture publications and is known for his sharp critique and narrative-driven features. At Arch2O, he highlights innovative architectural projects from Europe and around the world, with particular interest in adaptive reuse, public infrastructure, and the evolving role of technology in the built environment.