Sydney Opera House Conservation Takes a New Turn towards Robotics

Sydney Opera House is one of the world’s most prominent landmarks. Its story begins with the design competition held by the New South Wales government in 1956, in which the Danish architect Jørn Utzon’s entry, unexpectedly, won. Utzon’s idea was simple, but it had the constituents of a grand building, and so it caught the interest of Eero Saarinen who was a juror back then.

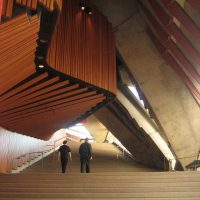

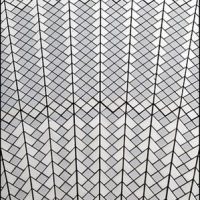

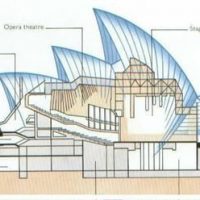

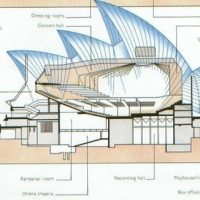

The Construction of Sydney Opera House began in March 1959 under the supervision of Ove Arup & Partners. Together with Utzon, they developed a structure system of ribbed precast concrete shells. These shells were cladded with 1,056,066 white Swedish ceramic tiles made of clay and crushed stone, resembling huge white sail on the deep blue ocean.

The building was finally completed in October 1973, with a final cost of 102 million dollars, exceeding the initial budget of 7 million dollars with a huge margin. In 1989, another 86 million dollars were spent on repairs for the structure system and cladding. However, all these expenses turned out to be worth it when Sydney Opera house was chosen to be a UNESCO World Heritage Site, making it on par with valuable historical sites like Taj Mahal and the Giza Pyramids.

As stated before, Sydney Opera House is covered by ceramic cladded concrete shells which need to be regularly maintained. So far, the technique that has been followed involved specialist engineers roping down the roof and tapping the ceramic tiles, checking for changes in their looks or sounds. It seems, though, that the time for this primitive and expensive technique is coming to an end.

Getty Foundation, along with the University of Sydney and Arup group are taking on the conservative operations of Sydney Opera House, as a part of Getty’s foundation “Keeping it Modern” initiative. The initiative funds conservative projects for modern buildings, the majority of which has employed new materials with unknown aging properties like concrete.

Monitoring the steel-reinforced concrete of the opera house is fundamental, in order to prevent any leakage that may result in cracks ruining the concrete and putting the whole structure at risk. The head of field projects at the Getty Conservation Institute, Susan Macdonald, explains: “It is often difficult to determine how well a concrete building is holding up until it the damage is already under way. The concealed position of the concrete, under a layer of tiles, complicates the problem.” To solve that, the researchers attached microphones and sensors to the tile-tapping hammers used in the tap tests, enhancing the quality of the information they gather. They are also researching the field of robotics with the aim of fully automating the examinations in five years. In this regard, Gianluca Ranzi from the University of Sydney says: “The use of advanced technology [developed as part of the project] has provided the basis for the development and prototyping of an effective inspection strategy applicable to 20th-century concrete buildings.”

The opera house’s chief executive, Louise Herron, is hopeful that these developments shall keep them on the right track. Macdonald has commended the Sydney Opera House staff for their continuous preventive conservation routine, saying that this is what they aim for in the conservation of Modern buildings, and adding: “We want conservation embedded at the core of the asset management plan.” Antoine Wilmering, a senior program officer at the Getty Foundation, agrees with Macdonald and adds that the Sydney Opera House conservation approach can be used as a model for other institutions.

- Sydney Opera House – Photography: Jozef Vissel

- Sydney Opera House – Photography: Jozef Vissel

- Sydney Opera House – Photography: Jozef Vissel

- Sydney Opera House – Photography: Jozef Vissel

- Sydney Opera House – Photography: Jozef Vissel

- Sydney Opera House – Photography: Jozef Vissel

- Sydney Opera House – Photography: Jozef Vissel

- Sydney Opera House – Photography: Jozef Vissel

- Sydney Opera House – Photography: Jozef Vissel

- Sydney Opera House – Photography: Jozef Vissel

- Sydney Opera House – Photography: Jozef Vissel

- Sydney Opera House – Photography: Jozef Vissel

- Sydney Opera House – Photography: Jozef Vissel

- Sydney Opera House – Photography: Jozef Vissel

- Sydney Opera House – Photography: Jozef Vissel

- Sydney Opera House – Photography: Jozef Vissel

- Sydney Opera House – Photography: Jozef Vissel

- Sydney Opera House – Photography: Jozef Vissel

- Sydney Opera House – Photography: Jozef Vissel

- Sydney Opera House – Photography: Jozef Vissel